Previous state

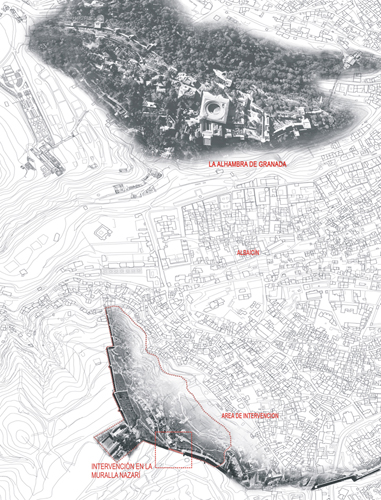

Near the Alhambra and the Generalife, beyond the Albaicín, rises the Cerro de San Miguel, a hill miraculously preserved as a wild natural area that provides one of the finest panoramic views over the city of Granada. On the summit is the chapel of San Miguel Alto, flanked by two stretches of Nazarí wall which have been conserved almost intact for over five centuries and follow the line of the city boundary. The wall and its immediate surroundings, populated only by fig trees and agaves, make up a green space that structures the relation of the city within the walls with the outside territory.Despite the ideal location of the zone, which was sunk in a state of total neglect, it was an unconsolidated urban sector affected by certain complex conditioning factors. First it is a free natural space, but residual and marginal at the same time. Second, new city sprawl in the shape of back-to-back houses with a strong visual and environmental impact has been creeping up the north-west slope of the hill since the 1990s and is coming dangerously close to the wall. Lastly, amidst this disorder, the wall is incomplete; in the 19th century an earthquake split the northern arm, opening a breach forty metres long, which can be seen from the Alhambra. The opening is used as a thoroughfare by the pedestrians and cars that move between the upper part of the Albaicín and the new Los Cármenes de San Miguel residential estate.

Aim of the intervention

In the face of this situation, in 2002 the municipal body Albaicín-Granada Foundation promoted an action involving an investment of a million euros, financed with European funds. The primordial aim is to preserve the place and prevent it from being built on and thus contain the excessive pressure of new urban growth. To achieve this, the project is structured along two main strategic lines. First it aims to domesticate the plant landscape and second to restore the wall and return its linear continuity.Description

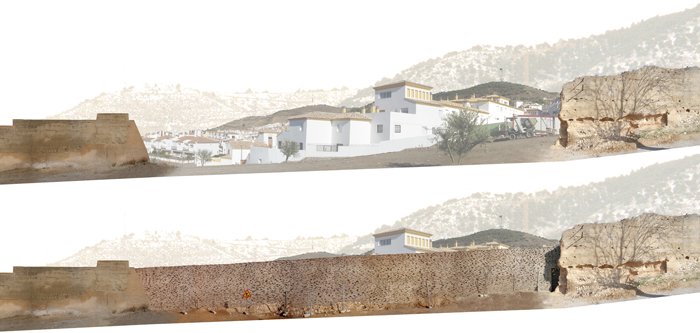

The recovery of the landscape of the Cerro de San Miguel begins with a general cleaning operation. The tons of waste piled up in the caves around the wall are replaced by new plantations of fig trees and agave. The facades of the chapel are restored and the state of the roads that connect it to the Albaicín is improved. In that way the fragments which still conserve the Granada paving are conserved and a soft rolled earth surface is laid where it has disappeared. The steepest stretches of the road are resolved with steps formed by large blocks of stone resting on the ground.For the restoration of the wall, the breach is closed with a filling that avoids direct contact with the historic remains and guarantees the conservation of the pieces of wall and the foundations. In contrast to the earth of the original walls and the masonry of earlier restorations, the plan uses an economical fabric of blocks of raw granite, of normal size, with a millimetre of high-resistance mortar. The new stretch of wall is exactly the same thickness as the old one. Now, however, taking advantage of the fact that its structural soundness does not depend on it being solid, the wall becomes a space that houses a narrow passage, eighty centimetres wide. The arrangement of the blocks of granite on the outer faces of the space leaves random gaps which, like a slatted blind, create plays of light and provide an openwork view of the city. At the two ends of the passage there are two gates that connect the two sides of the wall.

Assessment

Those two gates, which did not appear in the original project, are the fruit of the pressure brought to bear by the local residents, who looked askance at the disappearance of the old thoroughfare provided by the breach. Indeed the work, which was interrupted before completion, has aroused a full-scale media controversy in Granada, which has culminated in the surprising decision by the very City Council that promoted it to demolish it. The argument used to justify that decision is the inviolability of the heritage on which it claims the project is an attack.In fact this absurd idea betrays two attitudes which misinterpret the unfortunately ephemeral intervention. First it is a return to the intellectual obtuseness with which any actions on the heritage which are not mimetic are interpreted. Far from being an attack on it, the intervention is completely respectful. From a distance it gives visual continuity to the fabric of the wall and restores its lost historical boundary. From close up the restoration of the wall is undertaken from a contemporary standpoint which sets out to reconcile its historical significance with its present meaning, clearly distinguishing between what is preexistence and what is repair, but harmonising its appearance with the rest. Second, it reveals that the core of the controversy is not so much to do with the strictly architectural sphere as with the political one. Indeed, the municipal decision reveals the difficulty of setting limits to the urban development incontinence which is now ravaging many territories all over Europe. In some way the rebuilt wall would have been a containing wall for the urban sprawl, but now it is once again dangerously cracked.

David Bravo Bordas, architect

[Last update: 02/05/2018]