Logistical technologies make it completely viable to live without city. The pandemic has accelerated a logistical utopia.

One of the major challenges facing our cities is how to handle the impact of emerging logistical networks on the city. I’m referring here to new corporate time-space platforms that enable the swift distribution and circulation of people, goods and information in and around the built environment. For example, Amazon, Federal Express (or DHL), Deliveroo, Netflix and Uber, among others, have inched their way into our everyday lifestyle, with services that rely on sophisticated technologies and information systems that seamlessly co-ordinate flows in and around the city each day. Owing to the numerous lockdowns around Europe during the COVID outbreak (still happening as I write this), we have been fully immersed in a proto on-demand lifestyle. We shop and work online, our children learn through virtual meets, while subscriptions to streaming platforms like Netflix, Hulu and Twitch, among others, have soared, as we look to entertain ourselves while marooned at home. Even dying is a virtual act now, as funerals are streamed online. Logistical technologies make it completely viable to live without city. The pandemic has accelerated a logistical utopia.

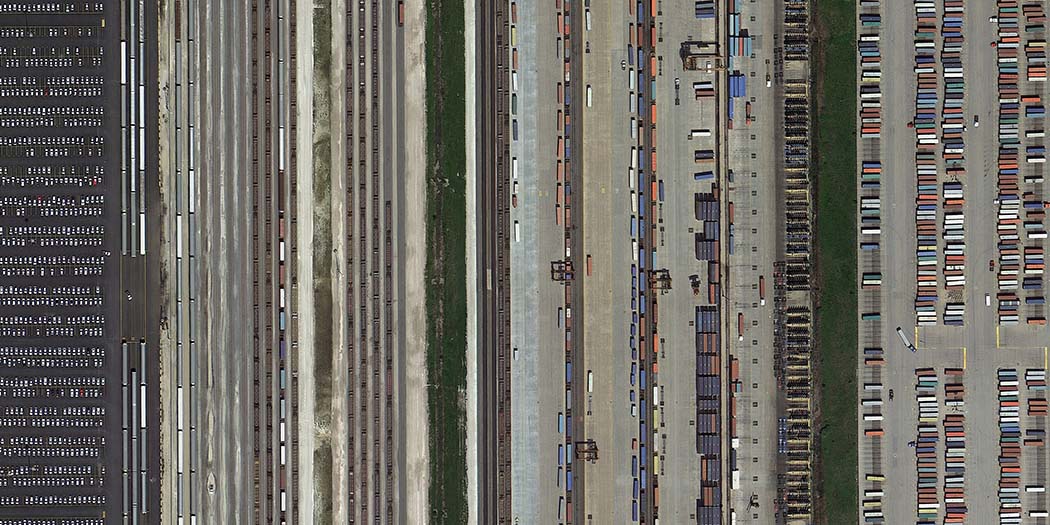

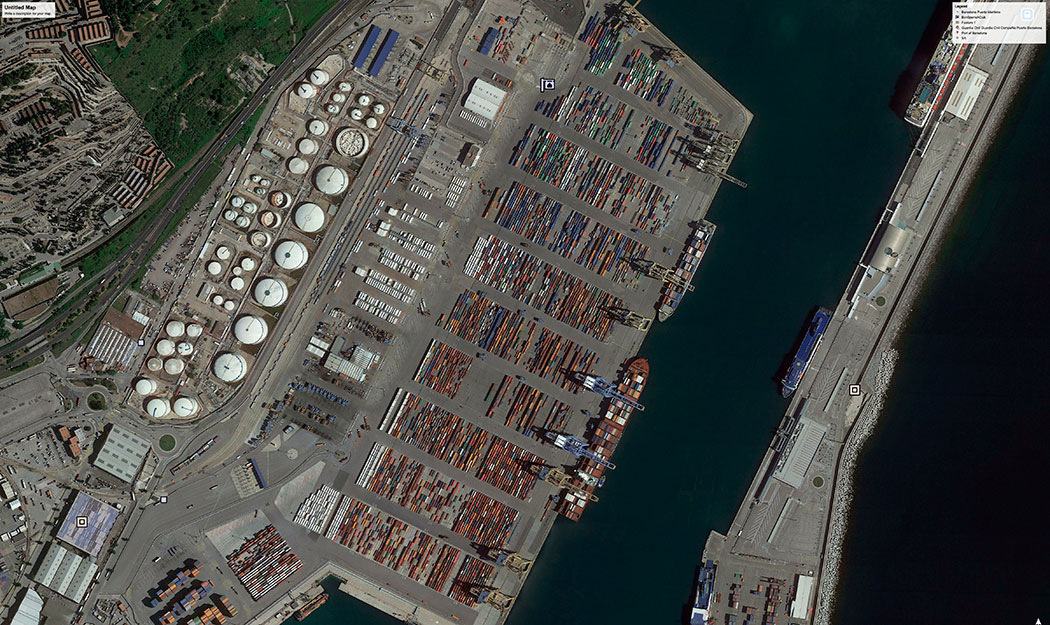

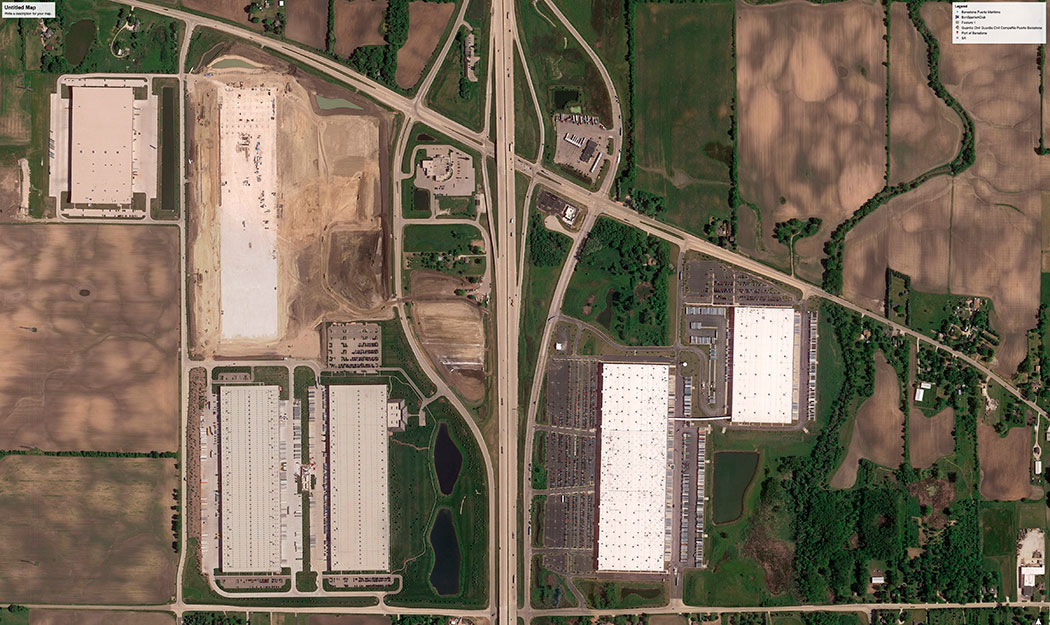

Or has it? Contemporary logistical platforms are an obstacle to public space, since their motivation is to skip or bypass the city in favour of on-demand services, brought directly to the home. Amazon ignores the high streets because it delivers straight to your doorstep. Uber disregards public transport by promising point-to-point connections. Netflix wants to eliminate the cinema in favour of online streaming to smart TVs or phones, in your own living room. Instacart replaces the food market, the locus of the city since Ancient Rome. Together, these networks are eroding traditional public typologies of exchange in the city—shop, theatre, office, church and school—and are thereby sucking life out of the community, as our city centres are supplanted by backstage infrastructural assemblages, from supersized automated port terminals and cargo airports to mega fulfilment centres and hyperscale data centres. The latter are now in rapid development, to be able to store the zettabytes of information that the logistical city needs to survive (figs. 1-3). Meanwhile, the corporate behemoths advance their hegemonic grip over our privacy and information, and they manipulate us into their rational world view.

Fig. 1. Port Terminal, Barcelona

Courtesy of logistics, the city is less and less the result of a set of formal procedures, expanding on the dialogue around the implications of post-war technologies in the city (i.e. dialogue that anticipated the complete dematerialisation of physical space, in favour of architecture and urbanism as a set of purely environmental and/or virtual effects). This means that the city is no longer the only mechanism that delivers us those things and services that traditionally mark a kind of urban lifestyle. Logistics now competes with, if not eclipses, the city as the dominant public space of our era, with its software and infrastructural appendages (from apps to RFID tags, from handheld devices to AI) that come together to allow incomparable access to an even larger notion of urbanity, one that serves the needs and augments the experiences of the everyday. Urbanity is no longer a destination in the habitual sense. Instead, it is recast as a series of simultaneously real and virtual exchanges—a hybridised service platform.

Fig. 2. Amazon Fulfilment Centre, Kenosha, Wisconsin, USA

Logistics has reduced the gap between public and private space. By enabling access to goods and services that were previously only available by going outside, logistics shatters concepts of interior and exterior. Logistics brings traditional urban typologies directly into the domestic or office environment and, by extension, successfully erodes long-standing boundaries between public and private. Such “cocooning” transfers urbanisation away from the city to the domestic environment and, further still, to the body. This is what Paul Virilio calls the citizen-terminal, i.e. somebody who is “wired to control his/her domestic environment without having physically to stir.” (1) There is no exterior, since the social organisation of the city and the household are now closing in. Body and city merge.

Fig. 3. Facebook Data Centre, Clonee, Co. Meath, Ireland

Yet:

Our logistical dependency, especially as witnessed during the lockdown, might well be efficient and convenient, but it’s far from ideal. In fact, one might say that the biggest lesson learned in the last year is that the technological utopia, as promised by logistical systems, is not quite so promising after all. We miss the exchanges of traditional public space; we crave the analogue, the chance meetings and the spontaneity of urban life. By accelerating our reliance on technology, we were thrown head first into the future, only to realise that the outcome is problematic—not only on a personal level, but also in terms of the city as a locus of community. Logistical platforms are only nascent. They will continue to dramatically transform the built environment, which impels us to consider new takes on where public space exists and how it is to be defined, moving forward. How can logistics be explored to reimagine new collectives? I offer the following speculations:

Neo-Nature

Post-COVID, we might return to old habits based on physical interaction, but the acceleration of technology into our daily routines will remain. Having an urban lifestyle delivered to our door is a new normal, and it is already transforming the use of public space. For example, the lockdown has given us a new appreciation of the outdoors, especially nature, not only because of social distancing. Being tethered to digital media has surprisingly unearthed our primitivity, so a renewed wish for escapism and authenticity, plus a more emotional connection to the simple things, is encouraging us to think about nature in new ways, as a sort of antidote to the frictionless efficiencies of platform living. An article in The Guardian, published late last year, reflects on the sudden robust wildlife ecologies that have been strengthened by our full immersion in the logistical life. (2) Isabella Tree, a British author and re-wilding expert who co-runs Knepp Wildland, a 3,400 acre estate in Sussex, highlights that, in 2020, white storks hatched chicks on the estate for the first time since the 15th century. Tree goes on to note that her estate, located near Gatwick Airport, 25 miles from London, witnessed a ten-fold increase in visitors compared to the same time a year earlier. Suffice to say, that if the city is no longer a social locus because it has been hurtled into the domicile, then public interaction must happen elsewhere, which explains why nature has suddenly been recuperated as an alternative venue for social exchange. While Tree is excited about the public’s new enthusiasm for nature, the increase in visitors to her estate brings its own challenges, in that more intense maintenance regimes are required in order to respond to the higher levels of human disturbance in the wild habitats.

New typologies of nature, from the repurposing of vacant post-industrial sites (as seen in many of the projects featured in the CCCB’s European Prize for Urban Public Space) to rewilding agricultural land, from upgrading and expanding woodland trails to frameworks for greenways and wildlife corridors in regional landscapes, will emerge as the new public landscapes of the logistical era. Trade your cappuccino for a pair of hiking boots. The forest is the new museum.

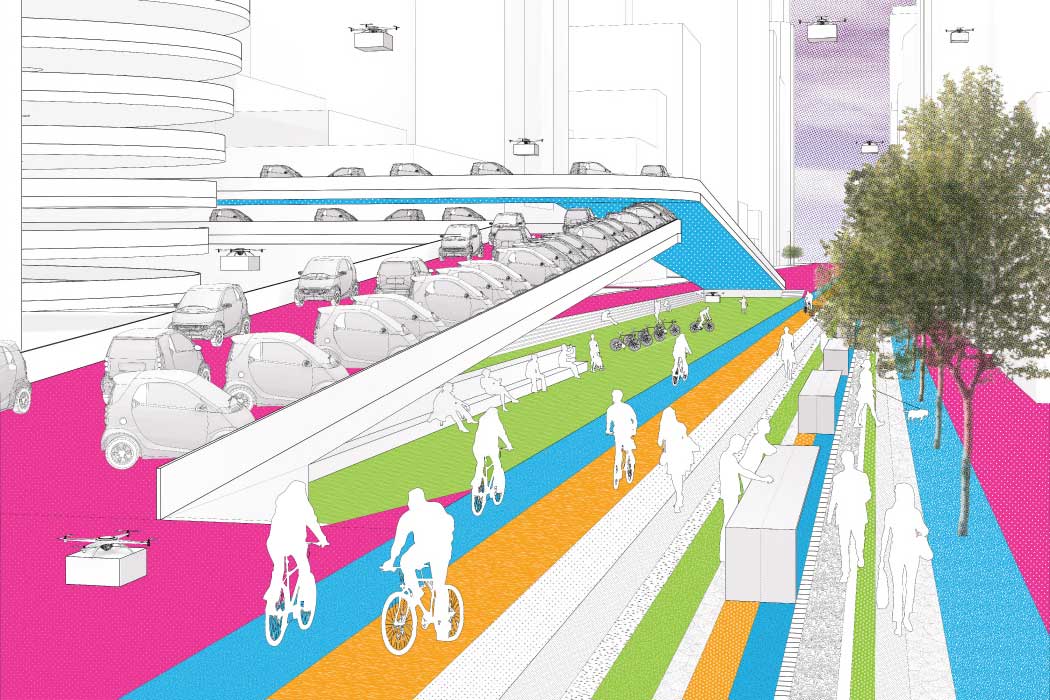

Fig. 4. Clare Lyster | CLUAA, After Shopping: The New Streetscape, 2017

Hybrid Integration

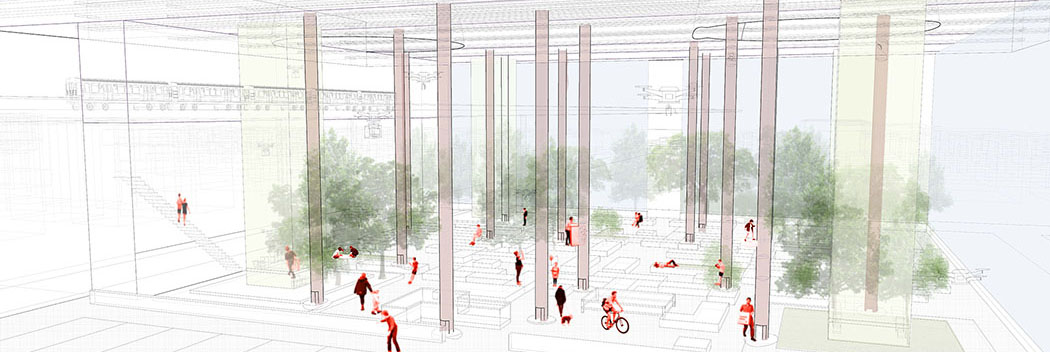

We can rethink public space by leveraging online platforms for the design of new typologies of hybrid space, when some physical presence in the city is still required to augment online exchange. For example, return kiosks, as well as logistical drop-off and pick-up nodes, constitute a hybrid space between the physical and the virtual, as well as the intersection of industrial design, furniture and urban space. This is already happening in the American city: retailers have responded to the rising demand for online shopping by installing refrigerated pick-up kiosks in their car parks, activated by a barcode on a phone, directly engaging the public with logistical systems (fig. 4).

Leveraging logistics for expanded synergies, on the architectural scale, is the motivation behind a 2019 proposal by OMA. It combines data storage with an art museum, to illustrate how the increasing digital archiving of artwork can catalyse the public use of a data centre. Furthermore, to quote the office, it can “merge storage and display into one integrated system”, proving that logistics and culture can indeed rub shoulders, with a productive outcome. (3)

Alternative Streetscapes

Shop closures, already a reality in the pre-COVID city, have emptied streets: ground floor retail, once the stimulator of urban renewal back in the 1980s, is disappearing, with competition from e-commerce and frictionless on-demand delivery. While many European cities still boast a lively café culture, due to robust inner-city populations, the American city, with fewer residents in downtown business districts, relies instead on the office worker. This worker, though, no longer plays a central role in the activation of public space, due to the surge in working from home.

Despite this, streets can still take on new lives in the absence of offices and commerce, though funding for revitalisation projects will be difficult without tax income from businesses. Ground floor spaces will need new programs—why not repurpose department stores for schools and housing?—but, given the current reduction of vehicular traffic, the pavements and paths are already taking on spontaneous usage, from roller skating to safer bike riding, as well as new gatherings and events. The street is no longer just a conduit for circulation, but a destination space in its own right (fig. 5).

Fig. 5. Sarah Rozman, Pick Up Plaza, The Logistical City Studio, UIC School of Architecture, 2017

Shared Collectives

Many of the typologies mentioned above proliferate logistical flows, and they accept, rather than critique, the hegemony of the logistical paradigm. It would be worthwhile to identify how logistics might be realigned for less capitalistic forms of space-making. On this topic, the curator Marina Otero Verzier writes of logistics: “The re-design and question of relations between space, time and political economy within them, could potentially result in other societal assemblages”. (4)

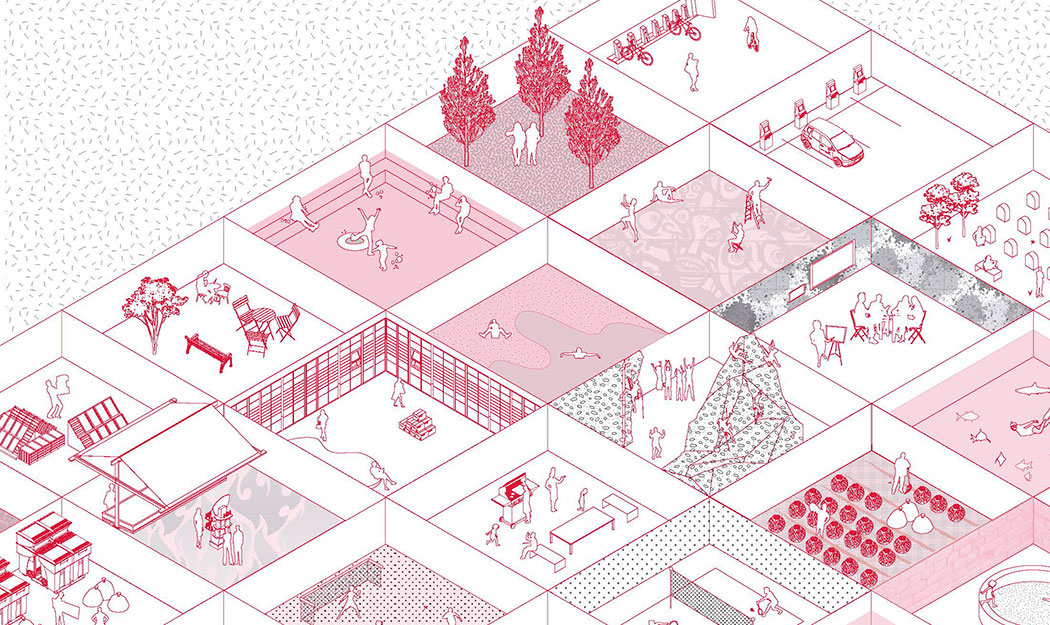

One promising realm for exploring how logistics can script other assemblages is in the domain of shared space. Here, the scheduling, efficiencies and real-time coordination germane to logistical technologies can be deployed toward a new spatial politics that promises more equitable and diverse uses of public space. New dedicated typologies of shared spaces in the city already include co-working and co-living, but these are still commercial enterprises. However, other assemblages outside consumerism and corporate control are possible.

Fig. 6. Yuping Sun, Shared City, The Logistical City Studio, UIC School of Architecture, 2017

For example, co-gardening is a useful way to think about stewardship of open space and the expansion of urban agriculture, allowing increased capability to split resources for more sustainable outcomes (fig. 6). An app that allows you to rent a garden for a period of time or co-farm a plot is one example: this not only advances the idea of allotment gardens, but might also help promote inner city densities that are badly needed to sustain the new forms of public space mentioned here. Shared Earth, a not-for-profit gardening platform that connects landowners with people who want to garden or farm (but who do not have access to land) illustrates how logistical technologies can smoothly organise the temporal exigencies of shared collectives in aligning online networks with new forms of physical interaction. (5) In summary, despite the challenges imposed by logistical platforms and their threat to the public realm, opportunities exist to re-script public space within the emerging socio-technical networks of our era. These initiatives might integrate logistics more readily into the city, or leverage its rational synchronisation for other ends.

(1) Virilio, Paul, La Vitesse de Liberation, Paris: Éditions Galilée, 1995 (English translation: Open Sky, London: Verso, 1997, p. 20)..

(2) Tree, Isabella, “Lockdown Initiated Our Awareness of Nature, But It Mustn’t Be at the Expense of Wildlife”, The Guardian, December 28, 2020: https://www.theguardian.com/commentisfree/2020/dec/28/lockdown-nature-expense-wildlife (accessed January 2, 2021).

(3) Koolhaas, Rem/OMA, “Museum in the Countryside: Aesthetics of the Data Centre”, in Young, Liam (ed.), AD # Machine Landscapes: Architectures of the Post Anthropocene, New York: Wiley, 2019, pp. 60-65.

(4)Otero Verzier, Marina, “Logistics”, AA Files, no. 76, London, Summer 2019, pp. 119-120.

(5) Johnson, Rebecca May, “Qualities of Earth”, Granta: https://granta.com/qualities-of-earth/ (accessed January 11, 2021).