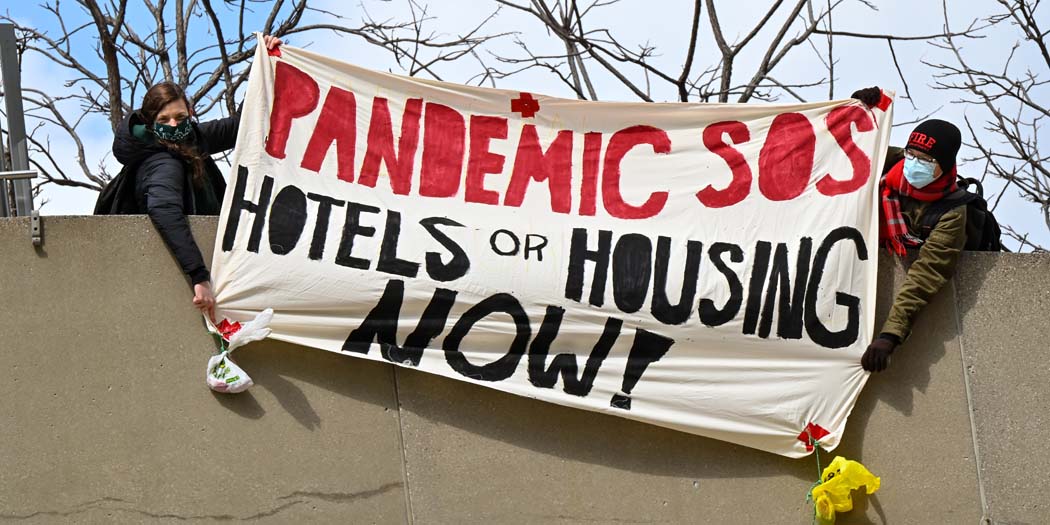

Air management is also a territory of macro and micro disputes of power, of political and ideological visibility.

Sometimes I wonder whether those conspiracy theories that claim some—perverse—tech company has implanted chips in our heads might in fact be true. Because, otherwise, how else would we have swallowed the idea that cities must be intelligent, that they must “harness” big data in order to be more efficient (which necessarily means a rise in the production of data itself, the more of it the better), and that we must fill our public spaces with gizmos to measure every single thing. They’ve been sneaking these ideas in through our ears without our even realising it, and, after hearing them again and again, something deep within our bodies has been triggered, and we’ve ended up accepting them as an inevitability. These are fanciful tales about better machine-cities built by “new” technologies, with public spaces connected by digital networks (which supposedly generate community), spaces that are efficient thanks to the three-dimensional deployment of all kinds of sensors. All of this works under the assumption that connectivity and efficiency are indisputable values. However, in reality, connections and networks are only for those who have the means, the time, and the body to be connected: essentially, connection for some implies exclusion and inequality for others. This approach also wagers that efficiency, as the driver of urban development, is not the crux of the wider problem: in this view, efficiency only means further squeezing the productive system, whether it’s a screw, a quarry or a human body, to produce more, usually for the benefit of a few. This doesn’t mean that efficiency of energy consumption isn’t desirable, but still it’s important to ask: efficiency of what, for whom, and, above all, at whose cost? Just ask the people who deliver food to your door.

Environmental monitoring networks and, in particular, air quality sensors, are the flagship technology of smart cities. They’re prime examples of the “Internet of things”, whereby machines communicate with each other to generate data which, seemingly with the swish of a magic wand, will reduce air pollutants. The idea is that simply knowing the data can lead to technical, political, and social measures being taken to achieve these aims, as if by magic. Yet it’s been proven that things don’t quite happen like that in the real world, partly because taking action requires, above all, personal and collective political will, and partly because altering the air is a very complicated matter.

In any case, measuring the concentration of a handful of gases and particles in the air does tell us something about the conditions of this shifting, often invisible mass which is a fundamental part of public space. It fills the space, it provides energy, it exchanges material with plants, humans, benches, bollards and clouds… it permeates everything, and regenerates dead bodies. Hence, sensors offer clues about the concentrations of ozone or nitrogen dioxide, but they also shape the air in the public space: its spatial organisation, use, accessibility and inequality.

The air-measuring sensors of the monitoring networks are installed in relatively large sites within the public space. They’re in the middle of footpaths, squares, parks, etc., taking up spaces that people have to get past, although they’re normally camouflaged and can’t be seen (just as the data isn’t seen either). In general, the data is accessible on local, regional, and state government websites. The Aarhus Convention on Access to Information, Public Participation in Decision-making and Access to Justice in Environmental Matters, which was signed by the European Union in 1998, requires member states to monitor air quality and give citizens access to the information. This has prompted NGOs—such as the Spanish Ecologistas en Acción— to carry out their own analyses of the available data, in order to ensure that governments are held to account, and to suggest possible solutions. And yet, how open or accessible does this data need to be? What happens when it is used to redefine house prices and, as a result, exclude even more people who are breathing in polluted air?

As socio-technical systems, sensors entail certain laws that stipulate responsibilities and rights. There are standards for the manufacture and calibration of such measuring systems, so that the data is comparable, and there are regulations for the acceptable limits of concentration for human health, among many other things. These limits have been used to offer citizens information about the real-time state of air quality by means of Air Quality Indices, as set by the World Health Organization. These limits, besides indicating whether the air quality is good or bad at any given time, also come with recommendations about whether—or not—to go out into the public space to do sport, or whether to cycle on alternate routes. Air quality indices therefore shift the matter of air governance onto individuals, recommending which bodies should be in the public space and which activities they should engage in, on the assumption that the default option is to stay at home. But who rides a bike? Who can afford to cycle on a different route if it means a few minutes’ delay? Certainly not those who deliver food by bike. Who can choose to stay at home? Certainly not the street sweepers, nor children who walk to school. And, of course, people without access to the data can’t make that decision either. So, these recommendations not only assume self-governance of our bodies, but they also shape inequality in the public space.

Over the last few decades, numerous projects have emerged with a view to addressing the limitations of open data, and to make the technology more accessible. By using cheap sensor kits that are “easy” to assemble, almost all of these projects aim to contribute by adding further points of measurement. These “do-it-yourself” sensors—also inspired by the Internet of things—have played a crucial role in highlighting the unequal distribution of air quality effects, and in providing evidence of environmental injustice in those areas without sensors or where the “official” data cannot be trusted. But they also raise a fundamental question: what exactly is the threshold for action to be taken? This isn’t about underdeveloped technology or a lack of data. Once it’s evident that the air of a given city is almost always very highly polluted, and that urgent action is needed on many fronts, why keep measuring?

The rise of a microscopic virus, spread by aerosols, has inverted the old ideas we once took for granted. Contamination isn’t outside now: it comes from within our bodies. The domestic sphere isn’t necessarily safe, whether it’s due to a lack of space, abuse, ill-treatment or exclusion, and, as far as COVID-19 is concerned, being out in the public space is “safer” than being inside anyway. Huge numbers of people have to leave their homes and go to work in poorly ventilated spaces, where they supply the key services that keep a city running. And they don’t have much say in the matter, because of precariousness and job insecurity. Furthermore, during the pandemic, management of the air in the public space has become a biopolitical tool, working in almost real time to prevent exchanges of air. Every day it is decided who must go out into the public space and breathe the air there, and why. Or who must not go there. Who has to be locked indoors, so they can’t share their air, and who has to go out in order to breathe. As such, how people breathe is managed, and the bodily orifices to be covered are defined: nose, eyes, mouth, skin. Access to the public space is assigned by hours, age groups, and, in some places, by gender, by activity (bikes, yes; games, no), by relations of cohabitation (two people, three people, bubbles of shared air), by distance (1, 1.5 or 2 metres; 5 or 10 kilometres), by geopolitical limits (neighbourhood, city, region, state, international corridors), by property limits (private, public), and so on. As a result, the air in the public space has become the territory of micro and macro power struggles. Of political and ideological visibility. And, out of everyone, all of this is disproportionately affecting those at the intersections between class, race, gender, economic condition and functional diversity.

Hence, SARS-CoV-2 has made it even more evident that air and social inequality go hand in hand. What’s at stake isn’t so much the quality of the air itself (which can certainly give rise to death and exclusion), but rather who can breathe, what they can breathe, and where. And what’s being done collectively about it. Because we are horrified—and half the world comes to a stop—when a virus won’t let white people breathe, but nothing happens when a policeman’s knee won’t let black people breathe. And kills them.

This doesn’t mean that measuring air quality is pointless, or that questions about the true usefulness of technology shouldn’t be asked, as happens in debates on the environment. Nor does it mean we should aim to go backwards, towards a prehistory where we rub sticks together to make fire, or towards an Edenic nature that never actually existed. This situation requires us to understand the present in detail, and ask what technology is to be used, and why. Also—and this is critical—what is the true cost of this technology, and for whom, whatever their species. Before measuring anything else, it’s vital that we comprehend who exactly is allowed to breathe in the air in the public space, so we can begin to plan for a future that’s worth living for everyone, humans and non-humans alike.