Previous state

Since 1950, when it ceased to be an independent municipality on being annexed to the city of Madrid, Vallecas underwent a process of exponential growth in order to take in a great number of emigrants coming from the centre and south of Spain. Today, when it consists of two districts that bring together a series of markedly working-class neighbourhoods, it is once again a reception zone for a second wave of immigrants coming from all around the world, with which it continues its process of vigorous expansion in a direction southeast of the capital.Since the 1990s, the Plan de Actuación Urbanística de Vallecas (Vallecas Urban Planning Action Plan) has been extending a new suburban development zone of square blocks spread over a surface of more than seven hundred hectares between the old town centre and the M-45 ring route. Although it was supposed to be completed in 2004 and is to be the site of 25,000 new homes, a considerable part of the Enscanche de Vallecas (Vallecas Urban Extension) still offers the bleak landscape of an extensive, reticulated, developed but empty urban structure. The streets, asphalted and named, the paved footpaths, the zebra crossings painted in place and the traffic signals and streetlights are all alone, awaiting the arrival of buildings and their future inhabitants. On the western side of the project is one of the more consolidated sectors, consisting of a dozen blocks under construction organised around the Bulevar de la Naturaleza, an avenue of some fifty metres wide and five hundred metres long running in a north-south direction.

Aim of the intervention

Although the boulevard had been built and, with some difficulty, opened to the public in 2004, the municipal housing company, EMV, called for entries in a competition for ideas on how to renovate it. The idea behind this surprising decision was to speed up the process of stimulating social activity in this public space, thereby advancing the definitive consolidation of the residential mass that it would have to nourish in the long term. The means by which it was hoped to achieve this aim was to make it especially attractive in the eyes of its potential users. Through the experimental use of eco-efficient systems that would respect the environment, the intervention was to offer a substantial improvement in comfort – in climatic terms with the hot, dry Madrid summers in mind – within this exterior space.Description

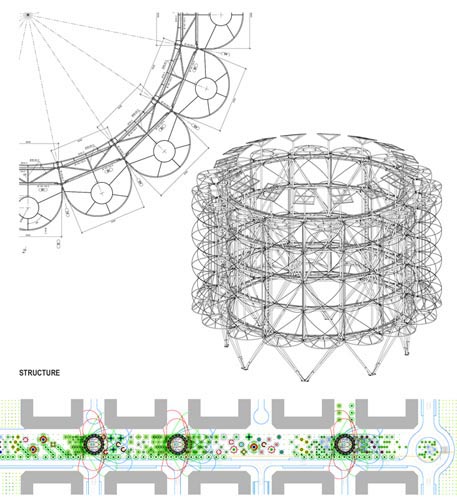

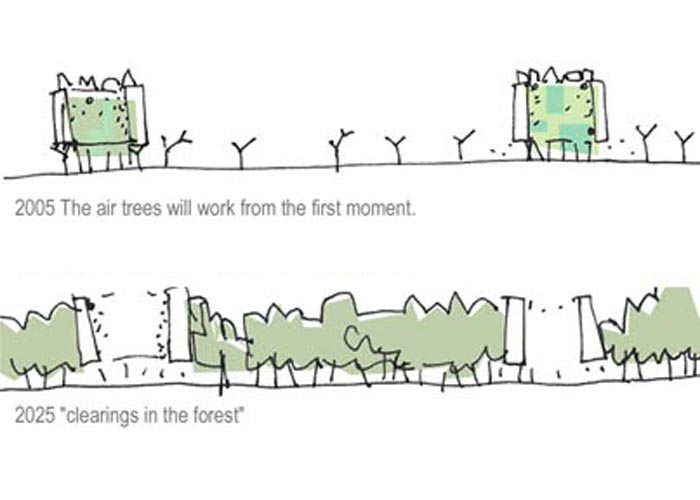

The renovation of the boulevard started out from the realisation that the best climatic conditioning of an urban space subject to this kind of high-temperature pressure had to come from tall, dense tree cover. However, the young trees planted along the length of the boulevard – which have been supplemented with new examples – will take another fifteen or twenty years to give the desired degree of shade and moisture. Hence, almost the entire effort of the project has been focused on a temporary installation along the thoroughfare’s main axis of three large bioclimatic pavilions called “air trees”.Partially constructed of recycled materials, each of these ephemeral, light and dismountable devices presents a cylindrical structure around a large empty space in the centre. Raised four metres above the ground, they reach a height of some twenty metres in total with an external diameter of twenty-five metres and an internal radius of nine metres. They are constructed over metal scaffolding that provides support for five superimposed polygonal walkways. These walkways are exclusively for maintenance purposes and contain pots with climbing plants that are to cover the interior surface of the central patio. The external face of the cylinders consists of a sequence of sixteen vertical tubular pipes.

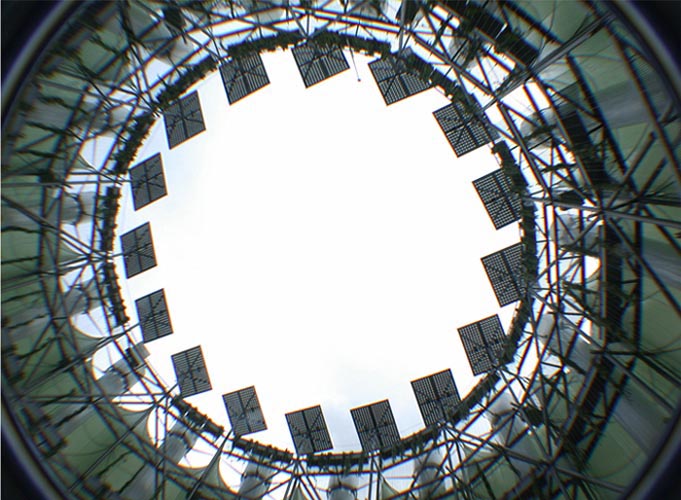

The pipes are crowned with adjustable wind captors that bring in hot air from outside. A fan is activated when the outside temperature rises above 27º C, pushing the air downwards. As the hot air passes through the inside of the pipe, it goes through a cloud of atomised water produced by the climbing plants and this moistens and cools it. This passive system, based on techniques of evapotranspiration which are normally applied in agricultural greenhouses, considerably raises the relative humidity and can bring the air temperature down by as much as 10º C. Each “air tree” consumes only the energy it is capable of producing by means of eighty square metres of photovoltaic solar panels which, besides powering the fans and the low-consumption night-time lighting, generates a surplus each year and this is sold to the general electric supply system as a way of financing its maintenance.

At the base of each pavilion, there is a cool, accessible circular space protected from the prevailing winds by a rammed-earth dune around the perimeter. This is finished with continuous paving of recycled rubber and equipped with benches. Presiding over this is the large central empty space of the cylinder, lined with the foliage of the climbing plants and covered with translucent sheeting which protects it from the sun. Once the time required for the tree cover in the boulevard to achieve the desirable height and density has expired, the empty central space could resemble a forest clearing. At this point, the “air trees” can also be dismantled and installed in another space that may need their services.

Assessment

Praised by some, the surprising presence of the three bioclimatic pavilions in a proto-urban space, which is controversial enough in itself, has also provoked other reactions tinged with mistrust or scepticism. On the basis of the argument that the most sustainable architecture is that which is not constructed, the honesty of their much-vaunted ecological qualities is put into question, the cost of their execution is decried as excessive or the artificiality of their marked character as constructed entities is criticised. Whether or not these charges are justified, it is not unusual for controversy to go hand in hand with urban elements that are as surprising as these “air trees”.The fact of stimulating lively debate over the solutions that architecture can contribute towards society’s adopting a more sustainable model is, in itself, positive. Approving or otherwise, the gaze of public opinion has been drawn to the Enscanche de Vallecas, which has started to take on its own specificity as a place on the map of Madrid. Whether they are sustainable cooling machines or places that stimulate social relations or not, the three pavilions do have the strange property of evolving over time. Their dual nature, both concave and convex, enables them to respond to the changes that their surroundings must undergo. At present, they are isolated objects, powerful urban landmarks that stand out in contrast with an empty, desolate space. However, it won’t be long before their central patios, or the clearings they will define if they are dismantled, will turn them into exceptional empty spaces within the desired density of a mass of buildings and vegetal cover.

David Bravo Bordas, architect

[Last update: 02/05/2018]