Previous state

Duisburg is a city in the Ruhr basin, one of Germany's most densely populated areas due to heavy industrial growth which took place from the mid-nineteenth century. The river Emscher runs through the Ruhr region and has two million inhabitants who live in 17 cities. It is known for the landmarks which bear witness to its important industrial past: mines and iron and steel works which are largely disused, and a road and rail network which crosses the region, next to the river Emscher which was channelled to provide a sewage collector.

The former iron and steel works, Thyssen Hochofenwerk Meiderich, located between Duisburg's Meiderich and Hamborn districts, was an example of the establishment of heavy industry in the Emscher area. Its facilities covered a surface area of 200 ha. and comprised a mining and coke-producing zone, the iron and steel works, cement tanks for materials as well as an extensive network of industrial railways. When the old Thyssen plant stopped production for good, in the mid-eighties, the site it had occupied, which was closed off and unknown to most of the residents in the surrounding area, revealed high levels of land and water pollution. In spite of this, the lack of activity had fostered spontaneous ecological renewal which gave encouraging prospects for new uses of the zone.

Aim of the intervention

The priority of intervening in a region undergoing an advanced process of deindustrialisation led to the creation of the body IBA-Emscher Park, in 1989. Its programme addressed the ecological and economic renewal of the area cut through by the river Emscher.

The programme was based on the conviction that future economic competitiveness should involve the ecological quality of regions and, in line with this, the main task of renewing the zone should seek to eliminate urban and ecological shortcomings in order to obtain a new basis for its future development.

The specific aims outlined by the body were: the ecological transformation of the fluvial system of the Emscher along a 350-kilometre stretch; the modernisation of workers' housing developments; the reassessment of old industrial sites; the conservation and reutilisation of industrial monuments as witnesses to history; and the preservation and reconstruction of the regional landscape. Indeed, the core topic of IBA-Emscher Park, during its ten years in existence, was the creation of a major landscape park in the Emscher region, a network of green spaces which needed to be preserved and linked up through new uses and new values given to old industrial sites.

The Duisburg Park, which is part of this territory, shared many of these aims as it stood for, on a local scale, the recovery of an important green area, the preservation of an industrial monument and the renewal of the river Emscher. Essentially, the park was to contribute to ecological renewal and give the broadest consideration to ecological reserves which could be made use of, and to strengthen cultural development and the shaping of identity both locally and regionally. It was also a question of improving living conditions and housing in north Duisburg through the creation of a large green space for public and recreational use.

Description

The site of the park comprises a surface fragmented by motorways, roads, railway lines, walls and industrial facilities where it is impossible to recognise an original landscape. For this reason, the intervention sought basically to recover a landscape shaped by former manufacturing industries and to open it up to new uses. The planning of the park had to anticipate the full complexity of elements featured on the site of the old iron and steel works and to work with all of them in order to create a public space with the main character of a public space. First of all, the difficult conditions of the site, due to pollution caused by industrial activity, were taken into account, as was the need to integrate ecological capacities in terms of the vegetation and fauna growing spontaneously on the site of the old Thyssen plant.

At the same time, it was decided not to demolish the industrial facilities of the factory -this would have been unviable for financial reasons- and to appraise it as a historic landmark. The demands of the residents' associations were also taken into account; they presented a number of options of a cultural and recreational nature.

These suppositions meant that the park was divided into a number of systems amongst which was the fundamental one: the water system. The channelled river Emscher which runs through the park has been regenerated due to the supply of rainwater which throughout its cycle, until it enters the river, utilises the factory’s old cooling tanks. One of the other systems in the park is formed by the railway lines which have been used to provide overhead walkways which run through the site and afford superb views of the area. The presence of the tracks together with other built elements mean that vegetation does not grow in a uniform way but is fragmented and has adapted to the characteristics of the soil.

For instance, vegetation similar to that of the steppes has grown on a surface comprising smelting materials, sand and ash.

The pollution of the land is visible in some areas but underground in others. A number of interventions have been carried out in order to clean it up, according to the type of pollutant materials. This means that there are areas where the land has been covered in new layers, but there are others which have been closed off and will be unable to be used until a long period of time has elapsed.

The main structure of the old blast furnaces now serves to illustrate the site’s industrial past; its great height means that it can be used as an observation deck for the area, and its centre contains an auditorium for large-scale concerts.

The Metallic Square has been built in the unoccupied space between the furnaces, formed by blocks obtained from the smelting of recycled material, which acts as a central area in the entire park and a venue for all kinds of events.

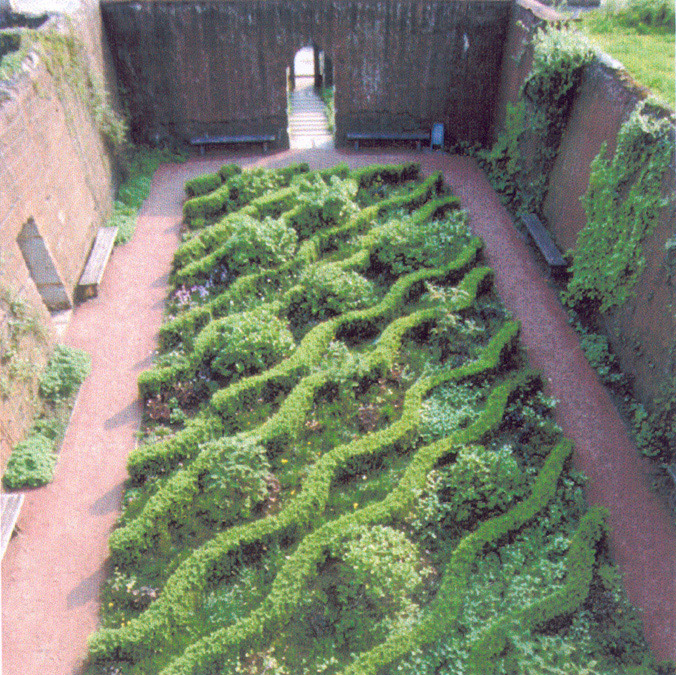

Furthermore, the disused tanks contain closed gardens where different kinds of plants grow. A walkway linking the different areas of the park enables us to view these gardens at the back of the tank structures. Steps and other means of entry have been made using recycled material obtained from the site.

The direct participation of residents’ associations from the area in defining the park is clearly shown in the use of the cement walls of the old material warehouses for climbing and the use by the scuba-diving club of the underground water which has penetrated the subsoil of the mineral strata forming deep caves. The club plans to convert the old gasometer into a large water tank where people can learn to scuba dive. The buildings at the entrance to the park house a small museum which illustrates the past of the site. It is run by a company set up for this purpose. Lastly, an educational farm has been set up on the south-east side of the park. It is aimed at schools from the neighbouring schools, and brings them into contact with animals and introduces them to a rural garden.

Assessment

The conversion of a site occupied by a disused mining zone and an iron and steel works in a landscape park involved a completely innovative decision without any previous examples.

In spite of the complexity of the enterprise, today everyone considers the old Thyssen factory a park with clear landscape values and an industrial heritage which has been converted into a new generation of park. The case of Duisburg should serve as an example to other similar cases which will succeed one another throughout Europe as deindustrialisation makes available land with major ecological shortcomings. The intention is to make greenery a dominant feature of the old industrial facilities in the park, but this will be a slow process due to the degree of irreversibility of the situation inherited as a consequence of the serious pollution levels of the site.

The park has also achieved its objective of opening up to the inhabitants a large-scale complex -previously only accessible to the employees of the iron and steel works- since the time when most of the activities performed there have been the result of residents' groups and associations in the zone. Today, all the surfaces in the park can be used freely, its is the venue for a varied range of cultural and recreational activities, and these will increase when the restoration of the disused power station has been completed. Its 5,000 m2 will provide an "indoor park" in winter.

Mònica Oliveres i Guixer, architect

[Last update: 07/06/2023]