Previous state

One of the last green areas left on the European side of the centre of Istanbul is Taksim Gezi Park, a public garden of some forty thousand square metres adjoining Taksim Square in the Beyoğlu district. The park was designed by the French urban planner Henri Prost, who was commissioned by President Mustafa Kemal Atatürk to carry out ambitious plans for modernising the city in the 1940s and 1950s. The park replaced the Halil Pasha Artillery Barracks, an Ottoman-style building which was demolished in 1943 in order to extend the free surface of Taksim Square. The square has been shrinking over the years with the construction of big hotels and, owing to poor maintenance, it has quite a run-down appearance.In 2013, the President of Turkey, Recep Tayyip Erdoğan, and the Mayor of Istanbul, Kadir Topbaş, announced sweeping plans for renovating the zone. The idea was to convert Taksim Square into a pedestrian area, to excavate tunnels for vehicular transport and to construct a replica of the old Ottoman barracks in Gezi Park. The new building was to house a large shopping centre on the ground floor, with a hotel and several luxury apartments on the upper floors. The announcement was made against a background of several months in which a series of government decisions had incensed ecologist groups. These included building several hydroelectric power stations in natural settings, constructing on land belonging to the Atatürk Forest Farm and Zoo in Ankara, putting a third bridge across the Bosporus, and large-scale deforestation to make way for the Erdoğan International Airport, the biggest in the world.

Aim of the intervention

On 28 May 2013 some fifty activists from different ecologist organisations set up camp in Gezi Park with the aim of peacefully blocking the imminent arrival of the bulldozers. The police evicted them the following day with inordinate use of water cannons and tear gas, as well as setting fire to their tents so that the demolition work could begin. The photograph of a policeman standing very near a young demonstrator in a red dress and aiming spray at her face was soon published all around the world, causing widespread indignation and making the “Woman in Red” famous as a leitmotif of the protest. Masses of people came and took the park. Besides the ecologists, the demonstrators included university students, families with children, people in wheelchairs, fans of rival football clubs, feminists, LGBT activists, defenders of Kurdish rights, socialists, communists, groups promoting laicism and anti-capitalist Muslims.Many of their demands, formulated some days later in a manifesto, sought to achieve guarantees of an effective right to the city and included the conservation of Gezi Park as a green zone, a total ban on the selling of public spaces, beaches, forests, rivers, parks and urban symbols to private companies and investment groups, and cancelling such projects as the new airport, the third bridge over the Bosporus, construction in the Atatürk Forest and the new hydroelectric power stations. The protestors also demanded democratic improvements, an end to police brutality and a legal inquiry into their aggression against citizens, an ethical and responsible press, and guarantees of the right to demonstrate to express grievances and demands without fear of reprisals, arrest or torture.

Description

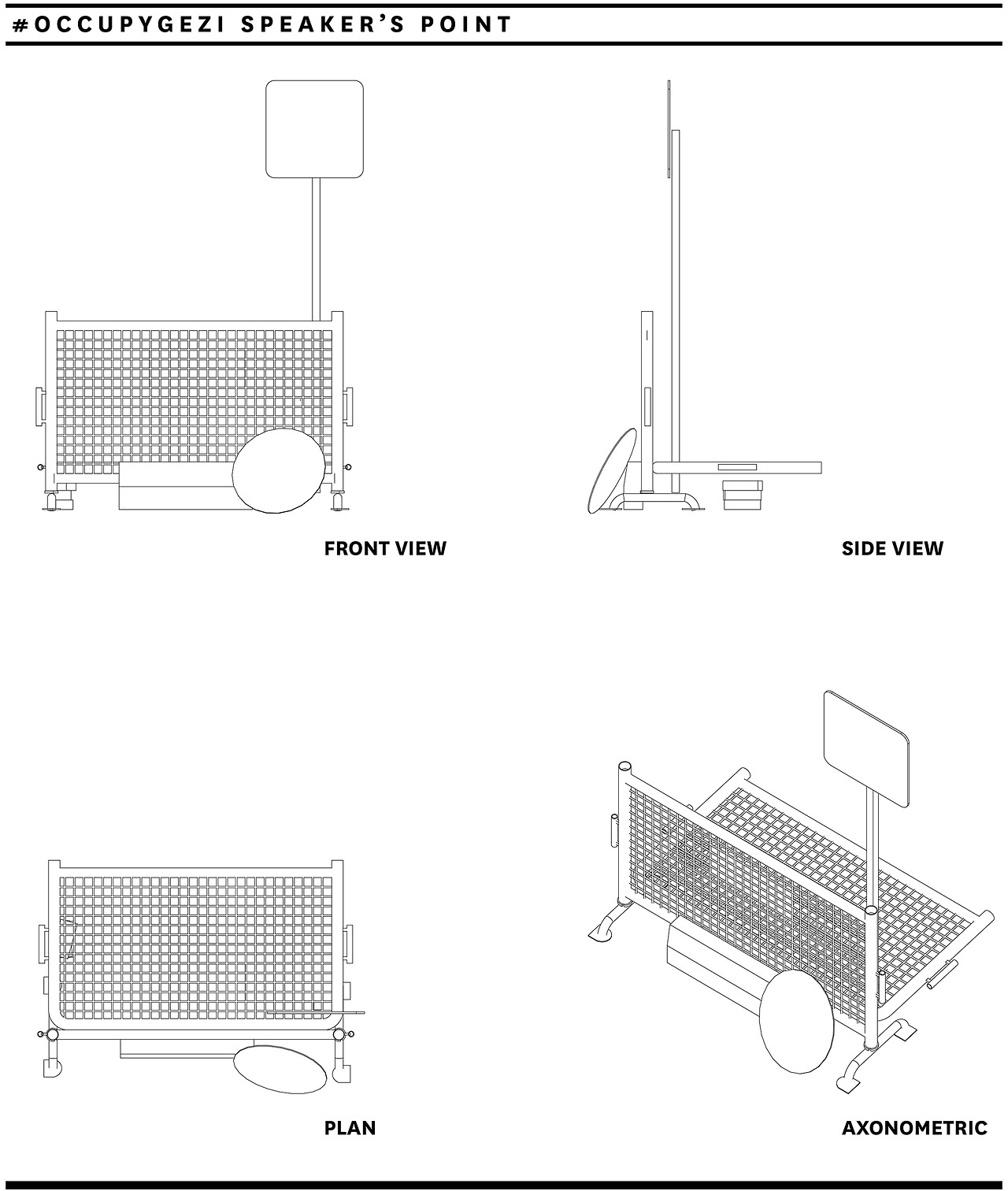

Nevertheless, the brutal police charges continued over several days with a toll of eleven deaths, more than eight thousand wounded and eleven thousand arrests. As the government crackdown worsened, the protest spread through all the streets of Istanbul, the cities of Turkey and in the mass media all over the world. The insults proffered by Erdoğan, who labelled the demonstrators “çapulcu” (“marauders” in Turkish) only encouraged them to keep on with what came to be called (using Anglicisms) “çapuling” or “chapulling”, which now referred exclusively to the struggle in defence of civil rights. The initial silence of the Turkish media was met with a sense of humour when many of the demonstrators started wearing T-shirts emblazoned with the words “We are all penguins”, referring to the fact that CNN Turkey showed a documentary about penguins while CNN International was providing live coverage of the protests.On 1 June, the police temporally desisted from their attempts to dislodge the protestors and break up the camp in the park, where there were now so many tents that it was necessary to put up maps at the entrances. By then barricades were being constructed from objects people had found and pieces of pavement in order to defend the campers from further police charges. The makeshift city offered many facilities to the community, among them a field hospital providing first aid, a canteen with volunteer cooks who organised their work into four shifts, a library with almost five thousand donated books, a vegetable garden, a market where products were given away, a cinema with a screen, a stage, microphones and power generators, a crèche, a yoga school and a mosque. There were also several remarkable public spaces. One of the main passageways was named after a Turkish journalist who was assassinated in 2007. A Peace Square was also opened, together with a forum for debates and assemblies, a playground for children and a “Speakers’ Corner”.

Assessment

Testifying to the political dimension of urban public space, the occupation of Gezi Park transformed a protest against an urban planning project into a historic struggle for democracy. It is estimated that more than three million people were directly involved in the biggest demonstrations Turkey had seen for decades, comparable with those of the Arab Spring (2010 – 2011), the Indignados (2011), the Occupy movement (2011) and even those of May ’68 in France. On 8 June, Mayor Topbaş publicly retracted and distanced himself from the decision to open a shopping centre and hotel inside the future replica of the old barracks, announcing that he was studying plans to go ahead with a public museum instead. A week later the Gezi Park camp was officially dismantled but the “chapulling” movement continued to apply pressure from other parts of the city and, indeed, from all over the country. Eventually, local and international social pressure obliged President Erdoğan to cancel his construction plans for the park. Surprisingly, although the decision was taken in mid-June, it was not made public until early July. Erdoğan also announced the setting up of an inquiry into police brutality. The policeman who attacked the “Woman in Red” for protesting against massive deforestation was sent to prison. His sentence included work planting trees in public spaces.David Bravo │ Translation by Julie Wark

[Last update: 18/06/2018]