Previous state

Owing, perhaps, to the enviable location of its port, Tallinn has had a chequered history which, taking its course in fits and starts, explains the lack of coherence in its urban and social fabric. Of Germanic origins, the city was notable as a Hanseatic League trading stopover on the maritime route connecting Western Europe with Russia. Dating from this period of economic boom, the impressive medieval towers of Vanalinn, the “Old Town”, contrast sharply with the modern mastodon-like buildings constructed on the periphery in the years of Soviet occupation. The USSR converted the city into its main cereal-exporting port, thus bringing about another period of considerable economic and demographic growth. The city’s ethnic complexity also grew as large numbers of Russian newcomers came to join the resident German and Estonian populations. During this period, when Tallinn was designated as the venue of the yachting events of the 1980 Moscow Olympic Games, the seafront, which was highly contaminated by direct dumping of industrial waste and sewage, was cleaned up and the Linnahall, a vast concert and sports complex was built, thus offering the city its first public access to a port zone that had previously been restricted to commercial and military uses.After 1991, once Estonia had recovered its independence, Tallinn underwent another economic boom, this time based on the new technologies and tourism. As a result of the former and fruit of the previous regime’s investment in the Cybernetics Institute, Tallinn has ended up being dubbed the Silicon Valley of the Baltic. The latter is mainly based on the two million Finns who, attracted by Tallinn’s proximity to Helsinki ─some eighty kilometres away on the opposite shore of the Gulf of Finland─ and the enticement of cheaper leisure activities in Estonia, arrive in the city by ferry every year. The economic upswing has led to major urban transformations that are, however, irregular in their scope. While a good part of Vanalinn, which was declared a UNESCO World Heritage Site in 1997, has been restored, mass tourism has ruined the atmosphere of some of its most significant corners. Furthermore, other parts of the city, for example the Linnahall complex and the seafront, have once again fallen into neglect. Meanwhile, still-existing tensions between the different groups in the population, both language-based and related with memories of the years of subjugation to Russia, are manifested in the divergence of meaning given to different symbolic points in the city. The violent disturbances of 2007, caused by the removal of a statue in homage to Russian combatants in the Second World War, were eloquent testimony to this.

Aim of the intervention

In recent years, Tallinn has tended to make the most of the summer break to host a wide range of festivals that promote social interaction and attract visitors. In the autumn of 2010, it was decided to organise an event called LIFT11, which was to be held under the auspices of the city’s being nominated European Capital of Culture 2011. The festival aimed to overcome ill-feeling related with public monuments in an ethnically divided city of disputed history, to offer new approaches to their language and revitalise their discourse by means of temporary installations located in different parts of the city. With this in view, a competition called for local entries. A Japanese architect was also invited to present his own proposal.The assignment did not preordain the exact sites of the interventions since choice of location and establishment of the dialogue therein was part of the challenge. The interventions were required to bring out the hidden values or latent potential of the different urban settings and to rescue them from banality, the a-critical gaze, and the chocolate-box kitsch of the tourist postcard. Many of the almost three hundred entries were designed by young creators who, to the surprise of the organisers, were overtly resolute when it came to highlighting the deficiencies of the prevailing urban planning and correcting its weaknesses. Ten proposals were selected and these, together with the Japanese project, were installed between June and October 2011, in eleven different urban interventions.

Description

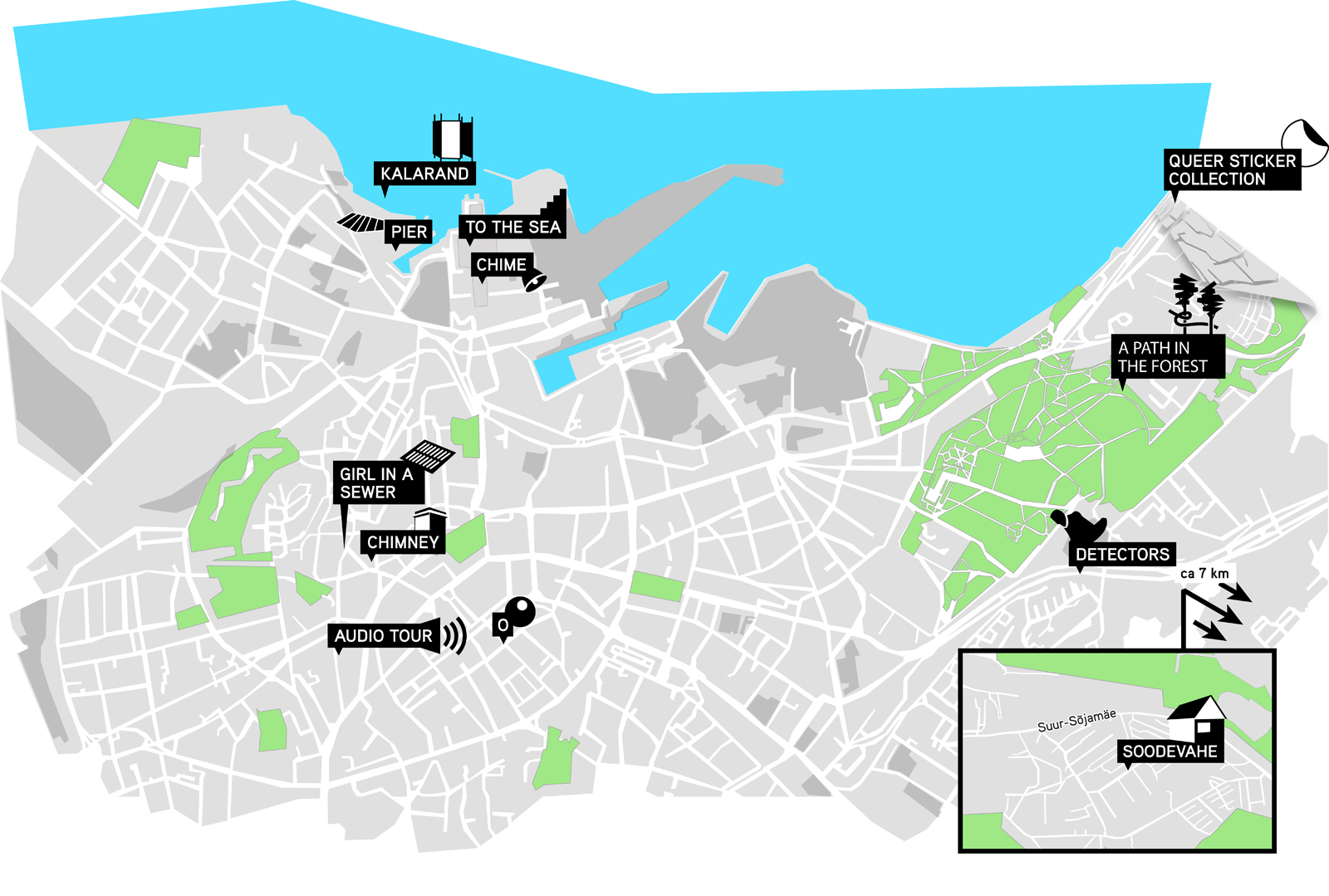

Four of the projects selected chose as their location the portside neighbourhood of Kalamaja (“fish house” in Estonian), present site of the Linnahall and once home to Tallinn’s oldest cemetery, which was demolished by the Soviet regime. These four interventions highlighted the zone’s potential because of its proximity to the coast and closeness to the city’s historic centre, while also denouncing its seriously neglected and run-down state. One, named “The Pier”, covered the pieces of a smashed concrete quay with wooden platforms, smoothing its surface and creating an area of waterside repose. Another, “Kalarand” (Fishermen’s beach), created a bathing area in a strip of the coast by fitting it out with platforms, changing rooms, benches and rubbish bins. A poster was put in place with information about the quality of the water and the site was ironically labelled “beach for swimming at your own risk”. Presented by residents of the area, this intervention was designed as a protest against plans to turn the beach into a boat haven and residential complex, while also reclaiming it as public space and an open swimming area. The other two projects for Kalamaja were direct interventions involving the Linnahall building, condemning as rhetoric the municipality’s promise to “open Tallinn to the sea” and protesting against the neglected state of the building. One of them, called “To the See” made its statement from the roof, where it erected a series of platforms offering splendid views across the Baltic Sea. The other, “Chime”, sought to attract visitors by hanging a fishing net full of small bells from the ceiling of the passageway crossing beneath the building.The three projects located in the Vanalinn historic centre aimed to rescue long-forgotten values or to give them new meanings. One of these, “O”, was a blow-up black ball of some three metres in diameter rolling randomly around the whole neighbourhood, blocking streets and passing over obstacles, thus surprising and leading to interaction among passersby. A mysterious sculpture called “Tütarlaps kloaagis” (Girl in the Sewer) ─an allusion to a poem of the same title by Juhan Viiding, a Tallinn-born writer─ was installed on the corner of Harju and Vana-Posti roads. This consisted of a pair of hands reaching out from a manhole cover leading to a sewer. The site is in front of the Café Pegasus in the House of Writers, once epicentre of literary life in the city during the Soviet period but now a shadow of its former glory. Finally, Roosikanstri Street was the site of an intervention called “Audio-Tour” which offered residents and visitors a chance to learn about the secrets of its historic buildings by means of a guided tour recorded on MP3. This could be downloaded on mobile phones and was also made available by means of playing devices provided gratis in the street.

The last four projects were more scattered, on the eastern fringe of Tallinn. The “Detectors” were two gigantic statues installed next to the motorway entering the Lasnamäe district. They consisted of volumetric figures representing two residents, scanned in three dimensions and simplified into flat facets by means of a computer programme. Once produced in a workshop, the facets were assembled in situ so as to form two monumental volumes that lent an extraordinary dimension to the everyday reality of a neighbourhood devoid of tourist attractions. Another intervention, titled “Soodevahe”, drew attention to the recondite, threatened values of the homonymous district adjoining the airport and occupied by a seasonal population living in illegal shanties. The plan to extend the airport, as a result of the tourist boom, included the demolition of this squatter settlement. In its last summer of existence, the inhabitants of Tallinn were invited to come and discover the charm of the area by means of a series of activities organised as a festival within the festival. This entailed restoring some shanties, setting up a plane-spotting observatory, the organisation of a garden contest, the opening of a café and theatre and the inauguration of SoMu (the Soodevahe Museum), which displayed material relating to the historic development of the zone, together with suggested alternatives to its destruction. The project called “Queer Stickers Collection” consisted of the publication of a free book of stick-on labels which, designed by different artists, invited people to personalise urban space by making transgressive claims on officialdom. The final work, “Path in the Forest”, by the Japanese architect expressly invited by the LIFT11 festival, was a walkway winding through the trees in the park of Kadriorg Palace, which was constructed by Peter the Great of Russia. The ninety-five metres of the walkway’s length were supported by curved stainless steel tubing resting tangentially on tree trunks in such a way that the absence of any vertical structure bestowed on it a graceful, delicate air.

Assessment

As if through an anthropologist’s eyes, the ephemeral LIFT11 installations cast extraordinary gazes on ordinary things. The festival thus succeeded in attracting many citizens to visit unfamiliar, forgotten or simply unnoticed places, getting them to see urban space from fresh, revitalised perspectives. The benefits of this exceptional summer in which Tallinn offered itself to an exercise of deliberate contemplation were twofold.First, the city was testing itself, temporarily becoming an educational laboratory in which practically everything was to be done because everything was possible. With their variety of scales, types, resemblances and durations, the installations adapted to the idiosyncrasies of their sites to reveal places of opportunity and rescue meanings lost in the mists of oblivion, while also bringing out the talent of the local artists who presented them. The new uses and senses bestowed on places and the forms by means of which people were able to approach them laid the groundwork and precedents for possible future work. They also challenged prejudices against public art and encouraged a general awareness of the benefits, costs and side-effects of urban interventions.

Second, LIFT11 had a democratising effect. Apart from protesting against some inexcusable negligences of the local administration, they called for a genuine recovery of the seafront as a space for everyone, highlighted the need to prevent the authenticity of the old quarter from being undermined by the pressure of tourism, and sought the inclusion of some peripheral realities in the official map of the city. Good media coverage ensured that LIFT11 sparked off debate as to the possibility of some of the eleven interventions, for example “Detectors” or “Path in the Forest”, becoming permanent fixtures. But, above all, it enabled residents of Kalarand and Soodevahe to use the occasion as a vehicle for democratic expression so as to make known their opposition to the government’s plans and to give voice to their hopes and fears. Finally, LIFT11 demonstrated the capacity of urban installations for promoting healthy civic promiscuity among people of different generations, ethnic origins and social strata.

David Bravo │ Translation by Julie Wark

[Last update: 18/06/2018]