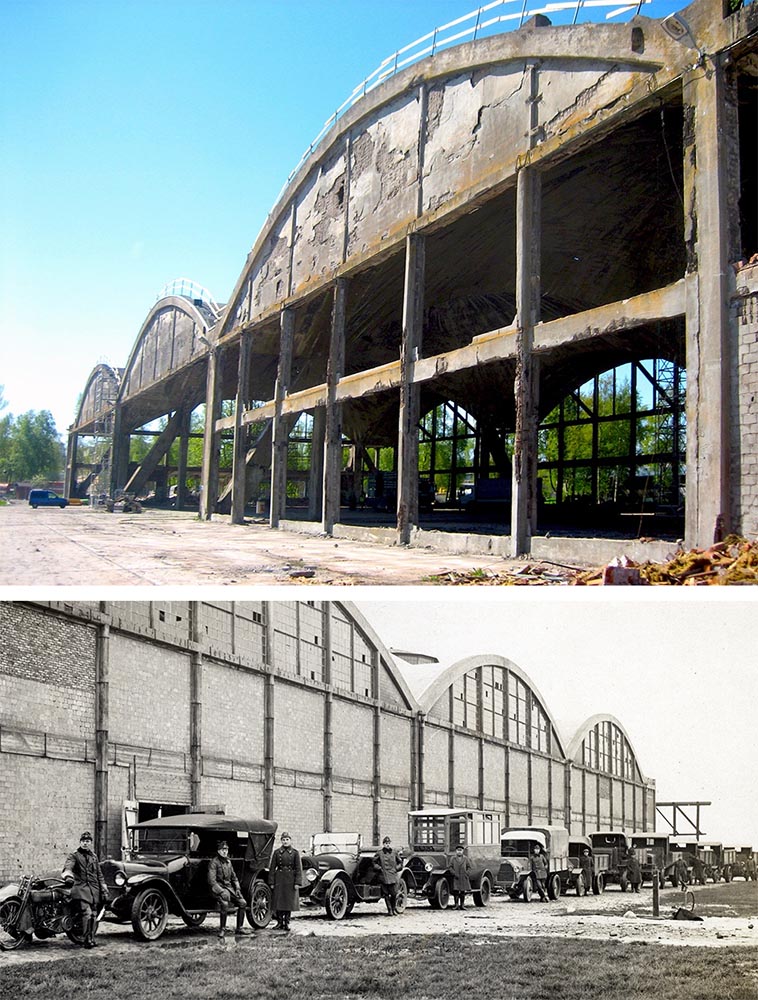

Previous state

It does not often happen that a seaside city should neglect its own coast, as Tallinn has done for more than a century. This sustained disregard is particularly evident in Kalamaja (“Fish House”), one of the city’s oldest portside neighbourhoods. Its relationship with the Baltic Sea was broken in the early years of the twentieth century with the construction of a naval base which was to become a strategic point on the western border with the USSR. The base was active until 1940, after which it became a military arsenal. Decades after the fall of the Soviet bloc, the Kalamaja coast was still of restricted access.Among the still-standing installations of the naval base is the seaplane hangar which was designed during the First World War by the Danish company Christian & Nielsen. This rectangular light-filled building with a single, open floor plan and a high ceiling has three huge reinforced concrete domes which, pioneering in their day, singled out the hangar as a landmark in the history of engineering. With a square base of some thirty-five metres across, they have an exceptionally fine thickness of only eight centimetres. Miraculously conserved after many wars, the domes were on the point of collapse at the beginning of the twenty-first century. They had lost considerable thickness in some parts and their steel reinforcement was visible and rusting. Moreover, the surrounding land was contaminated and, on the northern side, several keeled-over vessels lay on the docks which were badly eroded by the waves.

Aim of the intervention

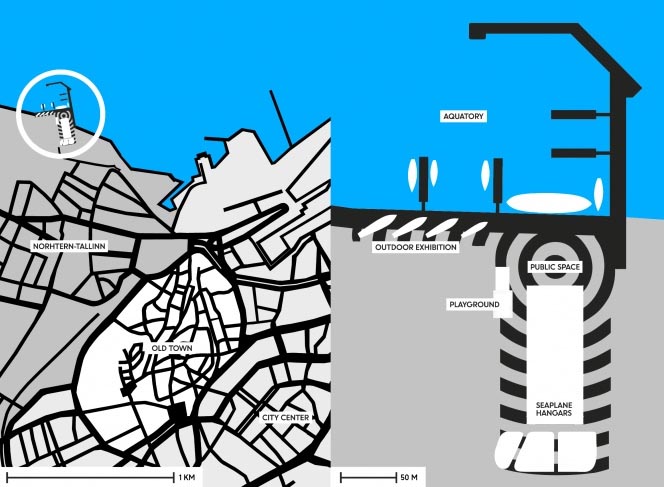

In 2009, after winning several legal battles against former Soviet officials who tried to reclaim ownership of the site, the Tallinn City Council saw a twofold opportunity in renovating the hangar. First, it would be rescuing a monument of great heritage value when it was on the point of disappearing forever. Second, the building held out the possibility of providing a large area of up-to-date space that would be appropriate for the collection of the Estonian Maritime Museum (Eesti Meremuuseum), the contents of which were then messily squeezed into an old building in the historic centre of the city.The naming of Tallinn as a European Capital of Culture in 2011 provided the incentive for moving the museum to the portside hangar, an operation which was achieved thanks to more than fourteen million euros provided by the City Council, the Estonian government and the European Union. The overhaul, which included both the building and its surroundings, was to bring the city and sea together for once and for all. This reconciliation entailed converting the old restricted zone into a maritime space that would be open to everyone so that people could now enjoy new facilities and activities in an area that had been neglected for far too long.

Description

The three domes of the seaplane hangar were scrupulously restored. The rust in the reinforcements was removed with high-pressure blasting, while the cracks in the concrete were filled with expanding cement. The ground surface they covered was left as a single, impressive, versatile space, although metal walkways were hung inside to organise the route of a three-level exhibition. At the lowest level are submarines, notable amongst which is the “EML Lembit” (1936), the only surviving vessel of the Estonian fleet prior to the Second World War. At the middle level are surface ships and, at the upper level beneath the domes, are the seaplanes, one of which is among the oldest in the world. A clear space has been left beneath one of the cupolas to be used for lectures and screenings.On the eastern façade of the hangar, there are three large openings with fold-up doors which open automatically every hour to flood the interior with natural light and make the museum’s contents visible from the esplanade outside. The land around the building has been decontaminated and it is now permanently open to the public. Wooden benches and metal lampposts have been installed and the area is paved with circular patches of granite in two tones of grey interspersed with parterres planted with grass. These areas of light and dark granite come together in the centre of the former parade ground, a square space located between the northern façade of the hangar and the wharf. It has now been converted into a square to be used as a venue for open-air events attracting large crowds, while also providing a vestibular space to the city for boats mooring at the wharf where a new portside promenade exhibits more boats and seaplanes. Some of these are part of the museum’s collection while others are privately owned and still in use, thus bringing everyday nautical activity to the area.

Assessment

Tallinn still has a great deal of work to do if the city is to be opened up to the sea. For the moment, however, a major step has been taken in the right direction. Opened in May 2012, the Kalamaja seafront has become an emblematic place which has now been visited by a third of Estonia’s population. Testifying to this popularity, more than 160,000 people attended the “Tallinn’s Maritime Days” festival, which was held in 2013.Moving the old Maritime Museum to the seaplane hangar has made the best possible use of two pre-existing assets. The project entailed establishing perfect symbiosis between the mutually dependent content and container. Justice is now being done to the museum’s collection in larger, modernised premises, in a setting that is much more in tune with the seafaring world. Moreover, a building of great heritage value has not only been saved from collapse but it has now been equipped to resume its old task of housing seaplanes.

David Bravo

Translation by Julie Wark

[Last update: 18/06/2018]