Previous state

The phenomenon of clandestine exhibitions, which proliferated throughout the Soviet Union in the years now known as the Brezhnevian Stagnation, made no exception of the capital of Moldova. Since underground art was prohibited and hounded by the authorities and its exhibition denied in the spaces of official culture, artists resorted to showings in private homes where groups of trusted people came together even though they ran the risk of being accused of “ideological disloyalty”. To the paradox of the stealthy exhibition was added that of people having to crowd together in flats of very meagre dimensions.Indeed, a good proportion of the homes in Chişinău were so tiny that they challenged the concept of habitability. After the 1940 earthquake and the Second World War bombing attacks, which destroyed 70% of its buildings, the city was urgently and hastily reconstructed by means of large reinforced-concrete housing blocks, described by regime propaganda as “good, economical and quick to build”. However, besides permanently changing the city’s appearance, the imposition of this industrial logic on urban and social fabrics had contradictory effects. Contrasting with the small dimensions of the new housing, the interstitial space between the buildings was so disproportionate that, even today, the figures for unoccupied land in Chişinău are among the highest for European capitals.

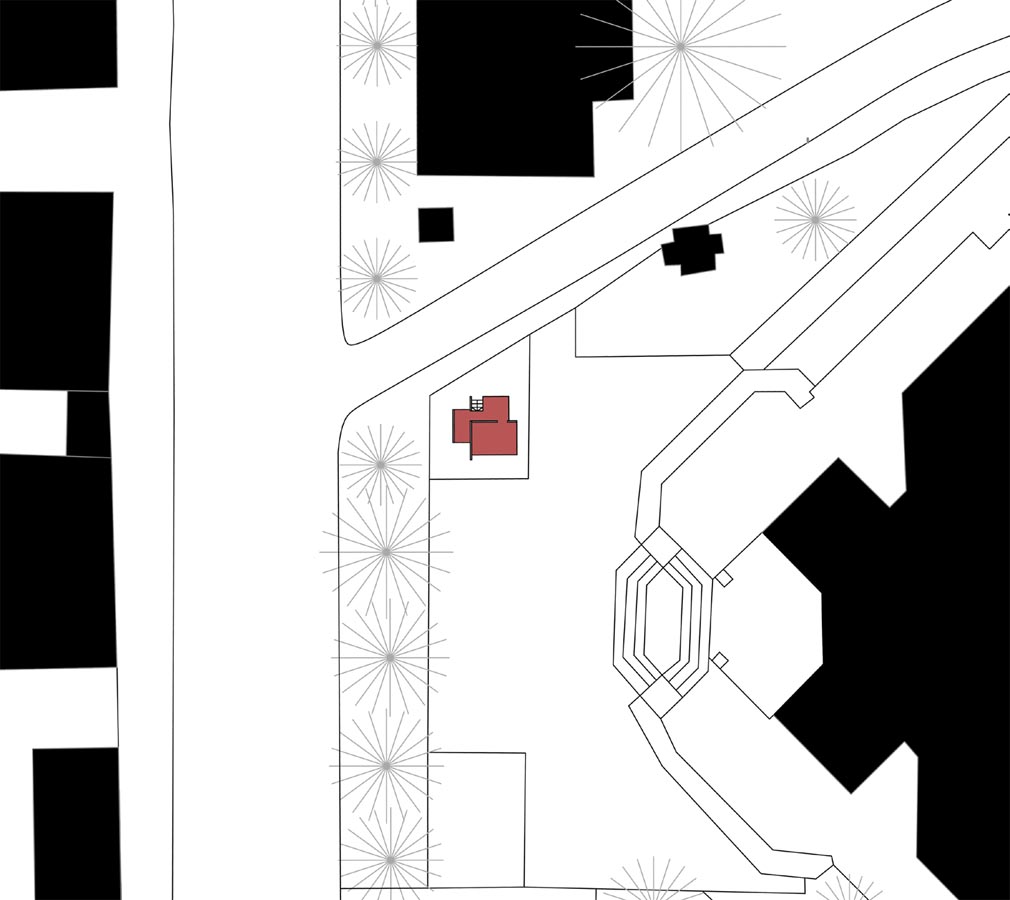

The market economy forcefully irrupted in Moldova after the country achieved independence, bringing about an almost total paralysis of state activity in the public sphere. Debilitated, discredited and lacking resources, the Administration has been unable to do anything about the city’s many empty spaces which, when they have not lapsed into a state of neglect and chaos, have been taken over for private profit or illegally occupied. The same thing has happened with cultural facilities, sporting areas, playgrounds, parks and gardens, which have been used for office buildings, real-estate projects, or erecting billboards, when not taken over as informal car parks. The municipally-owned esplanade located at number 68 Bucharest Street, just opposite the City Council’s Department of Culture, has met the latter fate. Absent from any Council agenda, this was a depressing-looking, run-down space, an image that was reinforced by haphazard parking and a dilapidated blind flank wall adjoining it.

Aim of the intervention

In 2008 an association of young artists, backed by the European Cultural Foundation and with the support of local residents, pioneered an alternative installation with which they took over the place and once again contradicted the official discourse. They called their project “Apartament Deschis” (Flat Space), in a deliberate word play between the notion of home (apartment) and the more immediate form of public space (flat place). It was a way of challenging the powers-that-be by calling for collective use of a derelict space and placing it at the service of art and culture.Specifically aimed at young people, the installation sought to found a meeting place, a space that would generate activities and promote citizen activity from the bottom up. It was necessary to open up for frank, critical and transparent discussion the urgent, unavoidable issues of public space and the city, to review the ongoing or pending urban transformations in Chişinău, to understand the cultural, social and political realities of other suburban areas in Europe, and to conceive of a project that would transform the esplanade itself. In brief, with a minimal budget and by means of a great variety of activities that would spread through the surrounding areas, the objective was to recover both the surface and sense of the place.

Description

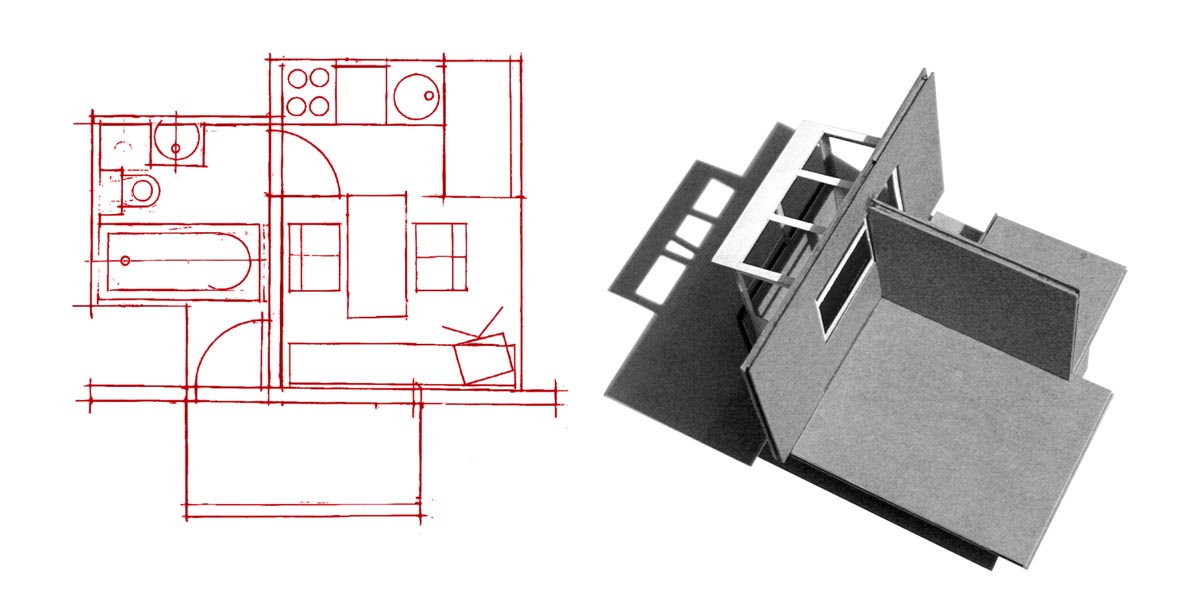

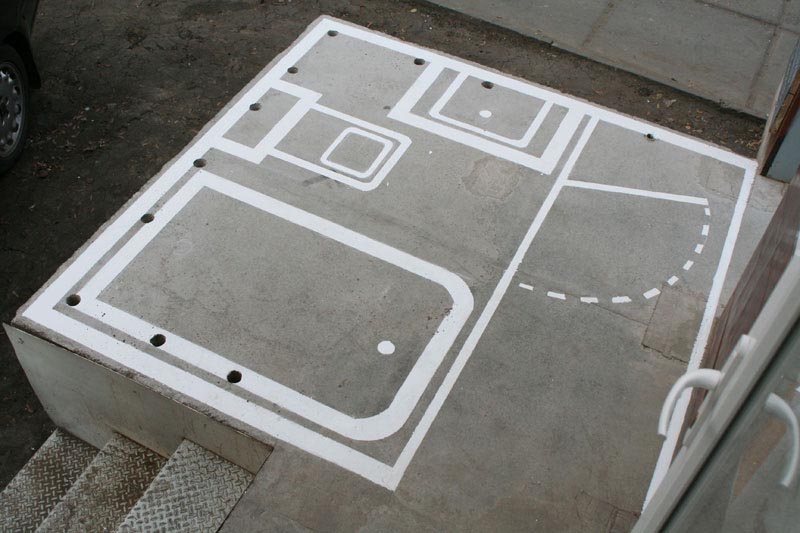

Flat Space, a literal replica of a functionalist apartment, has been laid out in the form of a kiosk on the paving of the esplanade. The installation is free of any bounds marking its perimeters so that it exposes to public view the intimate inside of a flat constricted by Soviet standards. It is slightly raised off the ground and, if its polyhedral geometry gives it a powerful visual presence, what it represents has a potent symbolic charge for anyone who has lived in a similar flat.It consists of a piece of the facade equipped with a small cement balcony, which has been closed off by means of poor-quality PVC carpentries to convert it into a glassed-in gallery. This has tended to happen in the Soviet-style housing blocks since the coming of capitalism, in a process whereby residents have personalised their homes, turning facades into mosaics of individualities that might be read as an expression of a whole society in transition. A transversal partition-wall runs from the façade dividing a space that is at once living and dining room, kitchen and bedroom from what would be the entrance and the bathroom. Some little steps lead up to the floor of the flat on which are outlined pieces of furniture and sanitary equipment so as to make the distribution comprehensible. Beyond the symbolic functions of this layout, the raised platform can also be used as an everyday information point and a stage for shows or public events.

Constructed with the help of local associations, artists’ groups, international volunteers and activists, the installation has also managed to commandeer its surroundings. Adding a surprising, out-of-the-ordinary feel to the space, artificial tulips and jonquils have been planted in the joints between the paving slabs on the esplanade, which was cleaned up, repaired and partially freed of cars. Illustrations have been hung from the adjoining flank wall and audiovisuals are projected on to it at night. After being recovered, the space has become a venue for exhibitions, conferences, concerts, screenings of video art and films, poetry readings, meetings with foreign students, second-hand and barter markets, demonstrations, a signature collection point, a meeting point for sightseers, writing workshops, and cooking courses followed by dinners, barbecues or mămăligă (traditional cornbread) tastings.

Assessment

With very little expense and in contrast with the common practice of decorating spaces without paying attention to content, Flat Space has created a monument out of precariousness. By means of recovering the subversive spirit of the museum-gallery-flats, which was as necessary when official art was a means of totalitarian propaganda, as in a present when art has become merchandise, the project therefore restores the most genuine sense of public space to a civic area that was formerly dominated by the representations of power or advertising. In shedding its facades, the domestic sphere casts off its condition as an enclosure ─or hideaway─ in order to participate with its surroundings, in solidarity with them. With this civic metaphor, the installation calls for shared spaces that are free of political control and economic barriers, where citizens can learn about and openly debate issues of concern to everyone. Such spaces continue to be an ineluctable requisite for the democratic health of our cities.David Bravo Bordas, architect.

[Last update: 02/05/2018]