Previous state

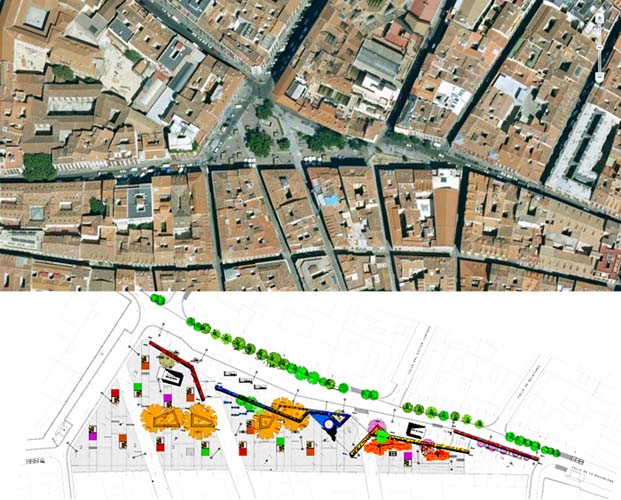

Madrid’s old Jewish Quarter spread out around the Plaza de Lavapiés [literally: foot wash] where, in the Middle Ages, there was a fountain at which the congregation observed the rite of washing their feet before entering the synagogue. This custom gave the square its name and, by extension the whole surrounding residential area. Ever since then, Lavapiés has taken in the most disadvantaged sectors of the population, thus acquiring a populous, lively and bustling atmosphere that is not, however exempt from marginal and conflictive aspects. Many of its inhabitants, with origins in rural Spain, settled there after the second half of the twentieth century. The run-down state of its buildings made them economically accessible so that, in the 1980s, they attracted a lot of students and cash-strapped young people, bestowing a bohemian air on the zone, while also ushering in drugs, indigence and prostitution. In the 1990s, of all the neighbourhoods of Madrid, this was the one with the most active squatter movement and, since the change of millennium, it has taken in a new wave of immigrants from all around the world, to such an extent that half its population today is foreign and the district is better known for its Chinese New Year and Ramadan festivals than for its Christmas festivities.In such a dense and cosmopolitan urban fabric, public squares are the setting in which the wealth of social diversity and the conflicts arising from this are most clearly visible. The Plaza Tirso de Molina has traditionally been a patent example of this. Located at the northern limit of the neighbourhood, half way between the Plaza de Lavapiés and the Plaza del Sol, it has a typically Mediterranean morphology. Its consolidated facades surround the empty space left when the old Convent de la Merced was demolished in 1836 as part of the seizure of Church property known as the Disentailment of Mendizábal. This was the last home of the Golden Age dramatist Tirso de Molina (1584 – 1648) who gave the square his name and whose statue is to be found there. With a drawn-out triangular shape, the square is delimited by the forking of the Calle de la Magdalena into Calle de la Colegiata and Calle del Duque de Alba. Moreover, almost ten transversal streets run into it and this, along with the fact that it has been the site of a Line 1 Metro station since 1921, means that it is a crowded place and a major point of access to the neighbourhood.

In recent decades, however, the increasing intensity of vehicular traffic hampered the circulation of pedestrians through the square. The three roads that surround it had several traffic lanes which, combined with the lines of parked cars, cut off the centre of the square which had effectively become the centre of a traffic roundabout. This isolated nucleus, which was only traversed by people going to and from the bus stops and used as a dossing-down place for the homeless, also housed the few trees that the underground railway and the traffic on the surface permitted to remain, while the rubbish and dirt piled up. The centre was a residual area that no longer offered the qualities required by a space for people to meet.

Aim of the intervention

In 2004, the City Council of Madrid set itself the task of recovering the Plaza Tirso de Molina for pedestrians. Starting out from a strategy that had the agreement of the residents and the socioeconomic agents who were most directly involved, the aim was to make the best of its strategic position and to restore its transversal flows of pedestrians and its capacity to act as a venue for activities from outside its area, which would be given priority over vehicular traffic. Apart from revamping its physiognomy and converting it into a pedestrian zone, the core element in this plan to recover the square entailed the establishment of a flower market. On the small scale, this new function was to infuse the interior of the square with life while, on the large scale, it would be given a special character that would distinguish it from the other public spaces in the urban setting.Description

On the western edge of the square the vehicle transit space has been reduced to a single lane that widens in one section to function as a loading zone. On the northern end, defined by Calle de la Colegiata, two traffic lanes have been conserved and a bus lane has been opened up to service the stops in the square. On the side delimited by Calle del Duque de Alba, the circulation of vehicular traffic has been eliminated. This has made it possible to extend the central area of the square through to the base of its southern façade, which is the most permeable of the three fronts. Five transversal, exclusively pedestrian streets start from here and lead directly into the Plaza de Lavapiés.Four long and slightly raised garden plots protect the zone that is now relieved of the din on the northern edge. The fact of their being raised vis-à-vis the slab that covers the metro enables them to contain the necessary amount of soil for planting, besides ivy and aromatic plants, new trees to complement the already-existing ones. Some of these gardens fold back on themselves to embrace distinct areas, for example a children’s playground, an entrance to the metro or the surrounds of the statue of Tirso de Molina. The continuity of the garden plots is interrupted at only three points to make way for the transversal streets that enter from the southern side of the square. The slabs of the new paving, which is fully accessible for people in wheelchairs, have a different finish in the areas that mark the continuity of these streets on the ground. All of them follow the line of the southern facade and define a pattern that regulates the placement of lampposts, fountains, games of hopscotch, table football, tree beds, benches and, in particular, the eight stalls that comprise the flower market.

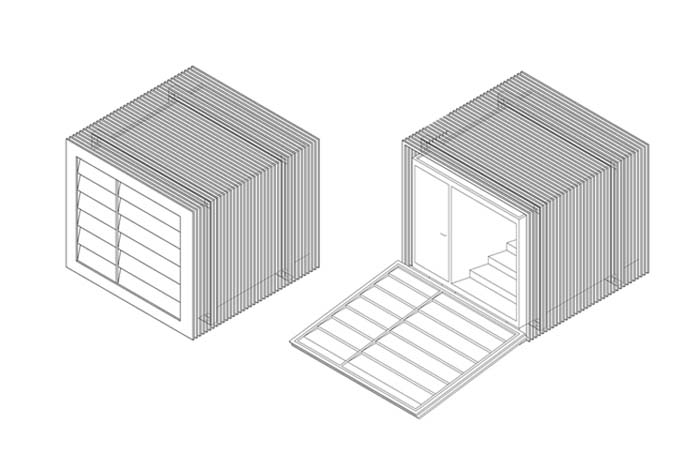

Each one of these stalls, in the form of cubic, wood-covered metal structures, has been given the name of one of Tirso de Molina’s literary works. One of the vertical faces can be folded down ninety degrees to create a platform on which the flowers can be laid out when the stall is open.

Assessment

All too often the refurbishment of urban space in a densely populated and conflictive neighbourhood uses the pretext of spectacular formal design to cover up a hygienically-minded desire to get rid of any evidence of social problems. The hypocrisy of such a strategy tends to result in domesticated, officially acceptable and aseptic spaces that are sadly alienated from the complexity that characterises the urban reality. The Plaza Tirso de Molina project does not resolve social problems such as indigence, drugs and prostitution – which continue to be present in the setting – but neither are they swept under the rug. In this case, contemporary formality has been put to good use to recover the traditional function of the square as a meeting place by means of substantially improving its accessibility and dynamism, qualities that contrast with its former status as the isolated, residual centre space of a roundabout.The accessibility of the new space is the result of overcoming the barriers that had been imposed by the private car and the possibility of its being crossed by the streets running into it. However, now it is accessible to everyone, the transversal character of the space needs to be translated into the transversal character of the social relations that are shaped there. The presence of the flower market means that the square is more a meeting place than a transit space. Open seven days a week, the flower market is the motor that vitalises the square and gives it appeal, thereby justifying the interest in making it accessible. The stalls, mostly run by immigrants, reflect the cosmopolitan diversity of the neighbourhood and provide a good pretext for interaction between the old population and the newcomers. As a meeting place, the square is a space of concurrence that acts as the backdrop for the agreements and disagreements that arise among the members of the society that occupies it, although it is not the solution to conflicts that may appear here.

David Bravo Bordas, architect

[Last update: 02/05/2018]