Previous state

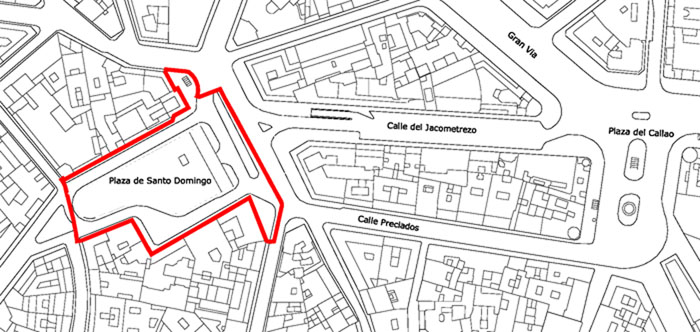

When Philip II moved his court to Madrid, the city which was then of middling dimensions, saw the arrival of a great number of court functionaries and servants. In order to house them, the monarch agreed on the “Carga de Aposento” (lodging levy) with the city authorities, establishing that the houses of more than one storey had to cede half of their surface. This resulted in the proliferation of “spiteful houses” of only one storey which, given their scant capacity also entailed rapid expansion of the built-up area. In the 16th century, the growth of the town was so abrupt and the land prices so high that there was neither time nor space to open up many squares.This situation went on until the brief reign of Joseph Bonaparte who, in the early years of the 19th century, was nicknamed “Rey Plazuelas” (Little Squares King) by the citizens of Madrid. Besides creating the celebrated Plaza de Oriente in front of the Royal Palace, the monarch, no friend of the religious orders, had several convents and monasteries demolished, thereby making space and giving names to new squares, for example Mostenses, Santa Bárbara and Santo Domingo. The latter, fruit of the demolition of a Dominican monastery founded in 1218 by Domingo de Guzmán, housed an open-air flower market until the 20th century when it was taken over once again, this time by a car-park building. With a difference in level of eight metres from one side to the other, the square followed a slope leading from Cuesta de Santo Domingo through to the neighbouring Plaza de Oriente and signalling, on the face of the city, the start of the Manzanares river basin.

Aim of the intervention

In recent years, the City Council has been engaged in a series of projects aiming to lay out a long pedestrian route in the historic centre of Madrid. La Puerta del Sol and the Plaza de Oriente are joined by the rectilinear axis of Calle del Arenal, where free transit of vehicles has been prohibited for some time. Now, the Council aims to complete this connection by defining an alternative pedestrian thoroughfare which, leading from la Puerta del Sol and going along Calle de Preciados, crosses Plaza de Callao and, describing a sweeping arc, opens into Plaza de Santo Domingo. From this point, one only needs to go down the Cuesta de Santo Domingo to reach the Plaza de Oriente. Calle de Preciados has become a pedestrian zone up to the point at which it reaches Plaza de Santo Domingo, where the building that partially occupied it has been demolished and an underground car park has been constructed. In 2006, a budget of two million euros was earmarked for the refurbishment of the car-park roof.Description

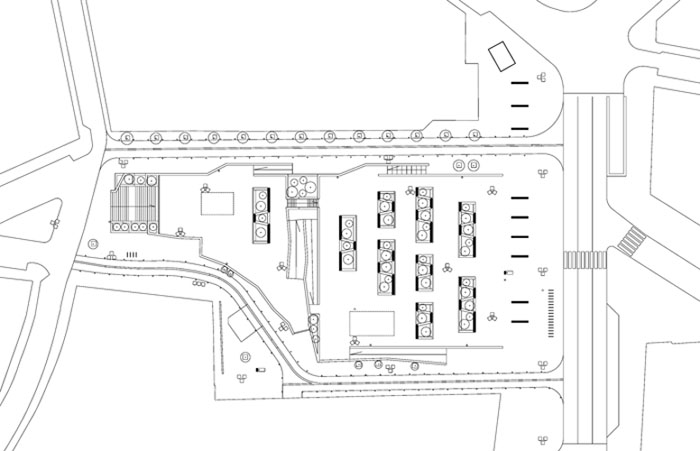

The central part of the new square is tiered into two large horizontal terraces. This means separation from the buildings that follow the topographical slope around its perimeter. On the northern side, the separation is made by the Cuesta de Santo Domingo itself while, on the southern side, it has been necessary to introduce a ramp that winds between the square and the buildings, giving access to the doorways and permitting a moderate flow of traffic.The higher terrace covers a more-or-less square platform with its eastern side at the level of Calle de Preciados. Given the slope of the land, the other three sides are held up by retaining walls with ramps and stairs to negotiate the different levels. It has eight parallel rectangular parterres amongst which trees and shrubs alternate with wooden benches. There is also a children’s playground area.

Some steps and a long two-section ramp lead from this platform to the lower terrace. Here, there is another children’s playing area and a ninth parterre, similar to the others. This second tier is at the same level as the halfway point of the ramp that winds along the southern end of the square. This means that both terraces are in contact. At the end of the terrace there is a stairway flanked by garden plots going down to the lowest part of the square and leading into the continuation of Cuesta de Santo Domingo. As part of an experimental initiative with other public spaces of the city in mind, the whole square has Wi-Fi Internet connection for mobile phones and laptop computers.

Assessment

The disappearance of the building that occupied a good part of the Plaza de Santo Domingo made it possible to offer continuity to the long pedestrian thoroughfare across the historic centre of Madrid. However, the project brought out the irregular topography of the terrain involved, which complicated the necessary achievement of a horizontal space for the activities and uses that characterise a public square. The mechanisms that were essential for rendering the slope into several terraces entailed the appearance of large retaining walls that interfered with the continuity of the route and broke up the quality of non-built-up emptiness that is required of a square.However, the project has been successful in treating these drawbacks as challenges. The accessibility of the whole surface of the intervention has been fully guaranteed, not only for people with reduced mobility but also for cyclists and baby buggies. This accessibility has gone beyond the physical sphere into the virtual domain by means of making available to the public such an increasingly essential service as Internet. Again, the raising of the platforms has made it possible to make an effective distinction between the circulation of vehicles at the perimeter and the central pedestrian zone. Moreover, in the downwards direction, the succession of terraces evokes the perspective one has from a belvedere while apparently raising the level of the ground, offering it up to the sun and the sky. In the opposite, ascending direction, the imposing presence of the stairs, the ramps and retaining walls reveal the irregular nature of the terrain that drops down to the Manzanares river basin and that, although it has been concealed beneath the built-up cover of the city, has been a determinant factor in the shaping of its morphology.

David Bravo Bordas, architect.

[Last update: 02/05/2018]